4 Reasons IT Projects Go Over Budget (and How to Fix Them)

IT projects don’t go over budget overnight. The overrun builds quietly through optimism bias, missing feedback loops, and compounding shortcuts. And the reporting that should catch it is often part of the problem.

Such patterns play out even in well-run organizations with disciplined teams. This article walks through the four most common root causes we’ve seen across 11+ years of rescuing and auditing software projects, helps you gauge how severe your situation is, and points to what to do next.

Key Points

|

Before You Act: A Framework for Diagnosing IT Budget Overruns

The right response to a budget overrun depends entirely on why it happened. Pouring more money into a project without understanding the root cause is the most expensive mistake you can make.

You’re facing a decision with three possible outcomes. You can invest more and fix the underlying problems. You can cut your losses and stop. Or you can scrap what exists and restart with a clearer scope.

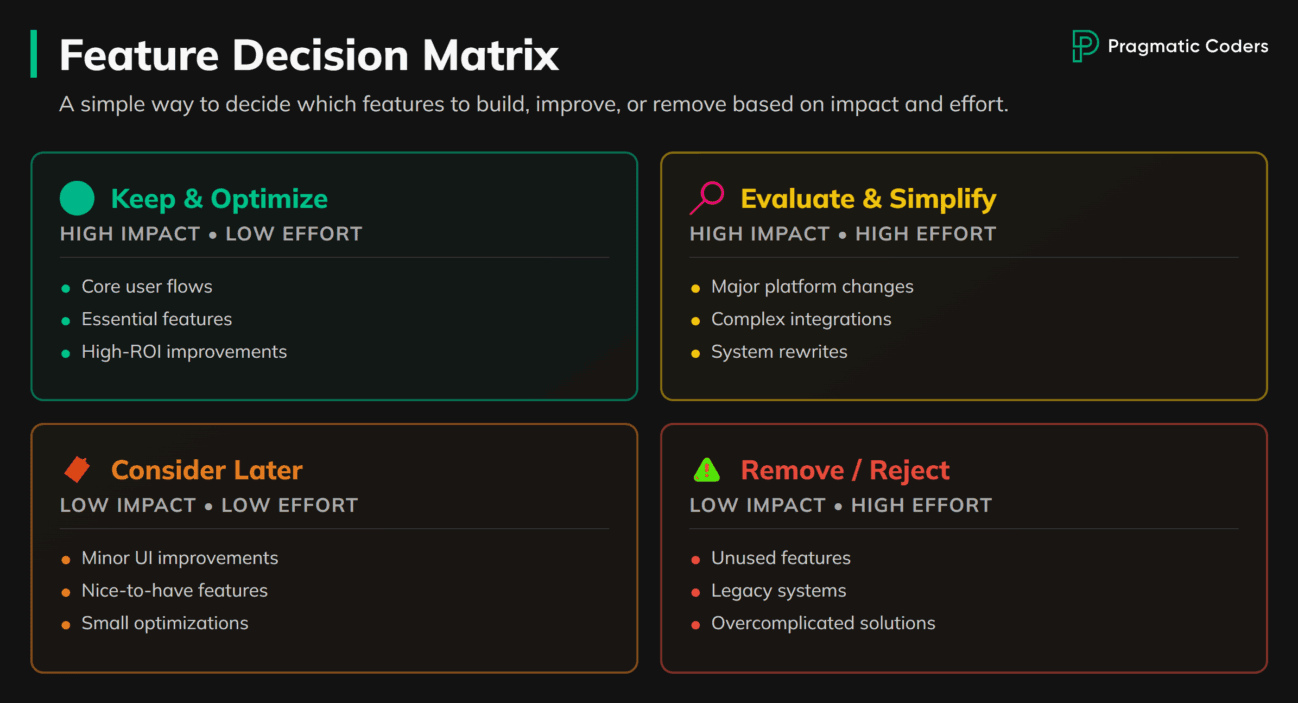

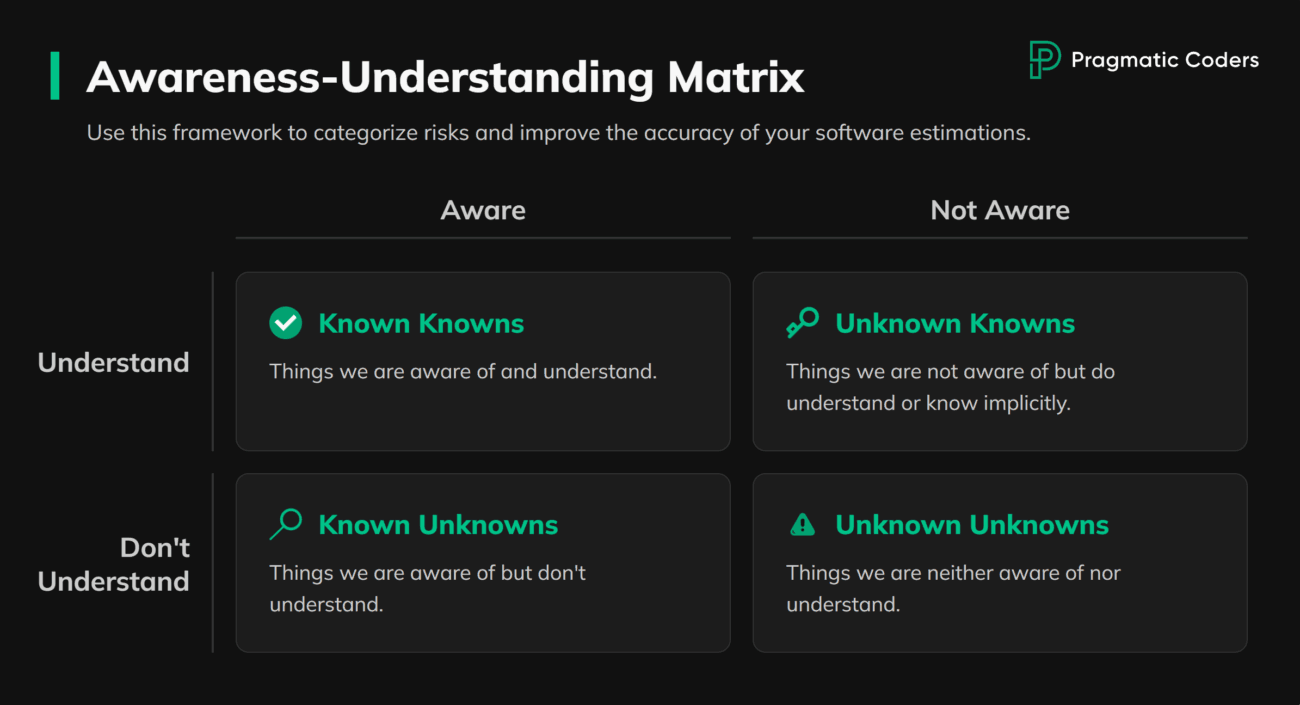

Not all causes carry the same weight. Some, like estimation gaps or a missing Definition of Done, are painful but fixable. You can correct them in weeks. Others, like an empty codebase hidden behind green dashboards or fundamental architectural rot, mean that every additional dollar deepens the loss. Each section below includes a severity gauge with at least one objective, externally verifiable check: something you can measure or request, not just assess by feel.

These same patterns show up whether you’re working with an in-house team or a contracted vendor. The dynamics differ, and so does the leverage you have. We’ll flag those differences where they matter.

One important caveat: these patterns rarely appear alone. Real overruns are usually a tangle of two or three at once. Scope creep feeds estimation failures. Tech debt hides behind watermelon reporting. The diagnostic value isn’t in finding one clean label. It’s in understanding which combination you’re dealing with and which pattern is the primary driver. The decision matrix at the end of this article addresses how to handle overlaps.

Scope Creep: The Number One Reason IT Projects Blow Their Budget

The team is building too much. Every “just one more feature” is a budget decision, and most teams make it without realizing they’re spending money.

Scope creep has many parents. External pressure pushes teams to match competitor features or say yes to every customer request. Internal dynamics create what we call the “executive decision-maker syndrome,” where leadership adds scope and nobody has the authority (or the career safety) to push back. Sales teams make promises to close deals. And unclear product vision leaves teams building something that’s perfect for no one. The psychology compounds it: each addition seems small (“while we’re at it”), but they accumulate, and the sunk cost fallacy makes teams reluctant to cut what’s already built.

Watch for the Feature Factory trap. Teams confuse Output (tasks closed, story points burned) with Outcome (actual business change). Nobody measures whether the work moved the needle. If your reports only track how much got built and not what changed because of it, scope creep has a perfect hiding spot.

With an in-house team, scope creep is often political. Saying no to your own VP is career-risky, so people say yes and let the budget absorb the cost. With a contracted vendor, the incentive flips: more scope means more billing, so the vendor has little reason to challenge your wish list.

A fintech client came to us with a brief for a real-time transaction analytics platform. Other providers had quoted $2M to $15M. The range itself, a 7.5x spread, tells you they were each scoping a fundamentally different product from the same brief. That’s what happens when nobody challenges the scope. Instead of adding another estimate to the pile, we asked what the client actually needed right now. The answer was a focused prototype to validate the concept and secure investor funding, not the full platform. Using user story mapping, we cut to the three highest-impact outcomes: roughly 10% of the original scope. The prototype shipped in three months for $80K and secured the next funding round.

The $80K isn’t the point. A different team might have landed at a different number. The point is that 90% of the original scope wasn’t needed for the actual business goal, and nobody had questioned it until then.

Is scope your primary problem? Recoverable if there’s still a clear core value proposition buried under the bloat. Severe if the product vision exists only as a slide deck, not as a filter the team uses to say no. Here’s an objective check: how many feature requests were rejected with data in the last quarter? If the answer is zero, you don’t have scope discipline. You have a wish list. And what percentage of shipped features are actually being used? If nobody’s measuring, the compass isn’t guiding anything.

What to do about it. If Brooks’ Law tells us that adding people to a late project only makes it later, the remaining lever is scope: cut to the 20% of features delivering 80% of value. We cover the full approach, from running a feature inventory to building request workflows that prevent creep from returning, in our guide to diagnosing and fixing feature creep.

Scope problems are visible if you look. The next pattern is harder to spot, because the reporting itself is broken.

How Misleading Dashboards Hide IT Project Failures

You may or may not be building the right things. You can’t tell, because reporting obscures reality.

The Standish Group’s CHAOS data puts the partial-or-total failure rate at roughly 66% across about 50,000 projects. The methodology has been contested: their definition of “failure” includes scope or timeline changes, which in Agile is normal iteration. But even accounting for that debate, the directional signal is hard to dismiss: green dashboards hide a lot of underdelivery because they track activity, not progress.

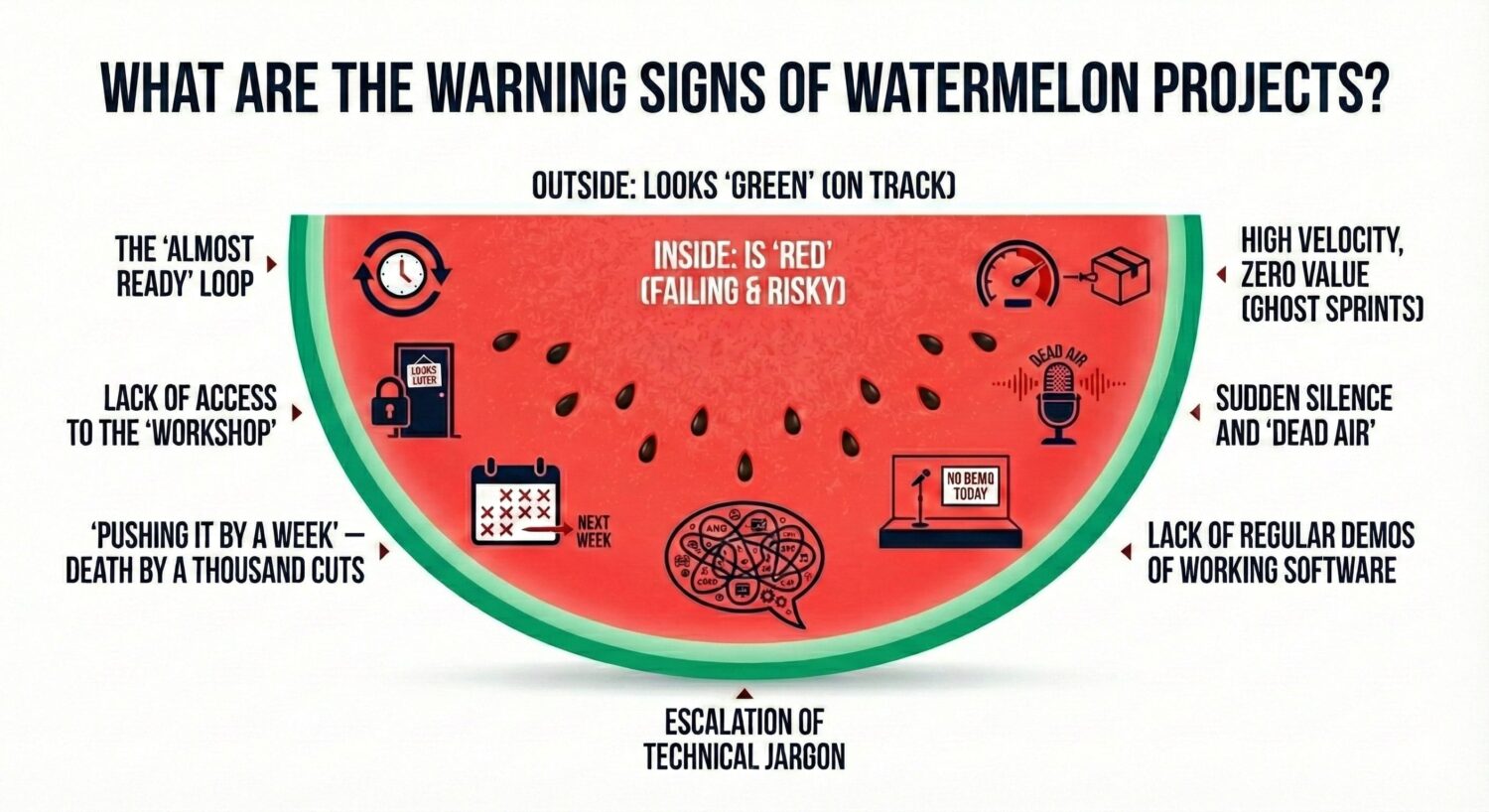

The Watermelon Effect and Why Teams Hide Problems

The metaphor is simple: green on the outside, red on the inside. Status reports show all-green while bugs, delays, and zero shippable progress fester underneath.

The dashboard stays green because it measures the wrong things. It tracks tickets moved and story points burned, not value delivered. A team can close 50 tickets in a sprint and ship nothing usable.

Why do teams hide problems? Programmer optimism is part of it. As Frederick Brooks noted in The Mythical Man-Month, “All programmers are optimists.” Estimates assume best-case scenarios. But the bigger driver is organizational. When red status means blame instead of help, people learn to report green. Add vanity metrics (high velocity, zero value), and the watermelon grows unchecked.

With an in-house team, fear of blame drives watermelon reporting. People protect their positions by filtering bad news. With a vendor, there’s a financial incentive to keep status green, and you may lack direct tool access to verify anything. If a vendor resists giving you live access to Jira or the code repository, treat that as a red flag in itself.

Seven Warning Signs Your IT Project Is in Trouble

These warning signs apply whether your team is in-house or external:

- The “Almost Ready” Loop. The feature is 90% done, every week, for weeks. In software, “almost ready” usually means the team hit a wall they can’t climb but are afraid to admit.

- No visibility into real work. With a vendor, you get PDFs instead of tool access. In-house, dashboards are curated before you see them, or nobody surfaces raw data proactively.

- Death by a thousand cuts. Every demo gets pushed “just one week.” Brooks wrote that projects rarely get a year late overnight. They get a day late, 365 times in a row.

- Ghost Sprints. Burndown charts look great, but business features lie idle. The team is closing simple technical tasks while the work you promised the board sits untouched.

- Communication goes dark. With a vendor, the PM becomes unreachable and vague. In-house, engineers skip standups, leads give vague answers in one-on-ones, and updates shift from specific to general.

- No demos of working software. You’re still looking at mockups after multiple sprints. The only objective measure of progress in software is working code.

- Jargon escalation. A 15-minute lecture on microservices synchronization to explain a simple delay.

The Deployment Gap: “Done” Doesn’t Mean Shippable

Tasks get marked “Done” when coding finishes, not when the feature is tested, integrated, and deployable. This is one of the most common hidden cost bleeders.

The Definition of Done gap is the core issue. “Finished” for a developer means “works on my machine.” For the business, it means “tested, documented, accepted, and ready for the customer.” Until these two definitions meet, your project is a watermelon. You can audit this gap directly by asking to see a feature marked “done” deployed to production on the spot.

How severe is this? Recoverable if it’s a process and reporting gap: the team builds real things, but communication is broken. Severe if progress has been faked entirely. Here’s your objective check: how many items marked “done” in the last sprint are live in production right now? When was the last production deployment? If you can’t get a straight answer to either question, that tells you more than any status report.

To detect this early, demand frequent demos of working software. The cadence depends on context: weekly check-ins, short async recordings, or more frequent touchpoints if trust is low. Look at raw systems yourself (CI/CD pipelines, repos, unfiltered backlogs) instead of relying on curated reports. Track leading indicators like cycle time, deployment frequency, and blocked-item age instead of vanity metrics.

Dashboard problems mask reality. But the next pattern silently inflates the cost of everything you build.

How Technical Debt Inflates Your IT Project Costs

Developers spend 33% of their time fighting technical debt (CISQ 2022). That’s roughly a third of your development budget going to the codebase instead of the product.

The Hidden Cost of Technical Shortcuts

Skipping tests, rushing architecture, or taking shortcuts looks like a saving on this sprint’s invoice. But technical debt works like a bank loan. You can take it to speed up, but the interest eventually consumes you. Every feature, fix, and change from that point forward costs more than it should.

If every sprint costs more than the last and you can’t explain why, this is probably why. When the board asks “why does everything cost more now?”, this is the explanation you can bring. It’s not that the team got worse. It’s that every shortcut taken in the past made the present more expensive.

How Technical Debt Shows Up in Your Budget

The symptoms are consistent across projects we’ve audited. Lead time keeps growing: every change takes longer and costs more. Small changes touch too much code, because tight coupling turns a trivial feature into cross-system surgery. Infrastructure costs rise without any corresponding increase in usage, driven by over-provisioning and architectural overhead.

Key-person dependency is a budget risk, not just a people risk. One person who fixes critical issues at 3 AM. A Bus Factor of one, meaning if that single person leaves, the project stalls. We call this Hero Culture. The hero gets rewarded for firefighting, but the organization depends on an irreplaceable individual.

Then there’s the normalization of pathology. “It’s always been this way” is the most dangerous sentence in software. Teams stop seeing bugs and delays as problems and start treating them as the expected baseline.

With an in-house team, normalization sets in and nobody challenges it. With a vendor, you may not even see the codebase. Vendor lock-in makes switching expensive. Ask yourself: do you own the repo, the infrastructure credentials, and the documentation? Or does the vendor hold the keys?

A case from our direct experience. One of our clients, a UK bank, had hired a Big Four firm that reported progress for nearly two years. When we were brought in to audit the codebase, the application physically did not exist. The code contained hundreds of empty methods with comments like “logic will need to be implemented here.” Millions of pounds burned on a facade.

How severe is this? Recoverable if the architecture is fundamentally sound but neglected: changes are slow, not impossible. Severe if every change breaks something else, Bus Factor is one, and there’s no automated testing or CI/CD. Objective check: what’s the average time from code commit to production deployment? How many production incidents in the last 30 days? Can more than one person deploy to production? If lead time is measured in weeks, incidents are climbing, and one person holds the keys, you’re building on sand.

What to do about it. Prioritize debt across four dimensions: velocity impact, business impact, risk and stability, and morale impact. Fix what hurts the most first. Set up quality gates in your CI/CD pipeline to stop new debt from piling on while you pay off the old. And make it structurally safe to surface problems: if mistakes get punished, people get better at hiding them, and hidden bugs age like milk, not wine. Concretely: run blameless post-mortems focused on process fixes, and give teams an explicit debt budget so fixing old problems isn’t something they smuggle in under feature work. We cover the full framework for classifying, prioritizing, and paying down technical debt in a separate guide.

Tech debt compounds quietly. The next pattern, estimation failure, is often what set the budget expectations that couldn’t be met in the first place.

Why Software Estimates Fail (and How Silence Makes It Worse)

A McKinsey/Oxford study found that large IT projects (>$15M) ran 45% over budget on average. The data is from 2012, skewed toward megaprojects, and the “56% less value” figure relies on executive self-assessment. But the pattern it describes, optimistic planning compounded by poor feedback loops, shows up at every scale we’ve worked at.

The number you were given at the start was structurally unreliable. Requirements change in 9 out of 10 cases after the first sprint. The initial estimate becomes fiction the moment real development begins. That’s not incompetence. It’s how software works: you can’t accurately price something whose requirements shift as you build it. The question isn’t whether the estimate was wrong. It’s whether the team adjusted transparently or let the gap widen in silence.

Estimation errors alone don’t kill budgets. Silence does. When poor communication compounds with the instinct to throw more people at the problem (which in a project already behind schedule adds overhead, not speed), small overruns become crises.

Pay attention to what you’re actually receiving. If the updates are heavy on technical justifications, forced optimism, or vague reassurances, the communication channel is broken. You should be getting the current state, the risks, and specific options with trade-offs. If that’s not landing on your desk, demand it.

With an in-house team, silence typically comes from fear of blame. With a vendor, from fear of losing the contract. The fix in both cases is structural. In-house: create a protected escalation channel where raising a red flag is expected, not career-ending. For vendors: restructure the contract so early disclosure isn’t penalized. Milestone-based payments that include “risk transparency” as a deliverable work better than penalty clauses that incentivize silence.

How severe is this? Recoverable if it’s a methodology problem: the team is honest but bad at estimating, and switching to iterative budgeting fixes the feedback loop. Severe if it’s a trust problem, where delays and cost overruns are being actively concealed. Objective check: were the last three missed deadlines communicated before or after the deadline passed? Can the team show you a velocity chart or burndown with real data, right now? If delays only surface after the fact and there’s no data trail, you’re not dealing with a methodology gap. You’re dealing with concealment.

Demand incremental budgeting tied to validated learning. Year-ahead estimates won’t hold; track against budget and critical paths to revenue after each iteration instead. Force explicit trade-off conversations: “What matters more, delivery date or budget? Will you reduce scope if needed?” If your team struggles to structure these updates, we’ve written a framework for communicating project problems you can hand them directly.

Now that you’ve assessed each pattern individually, how do you combine those signals into a single decision?

How Severe Is Your IT Project’s Budget Overrun?

Each section above included a severity gauge with an objective check. This section turns those signals into a decision.

You’ve already gathered concrete indicators: your feature rejection rate, your last production deployment date, your commit-to-production lead time, and your deadline communication history. Now combine those signals into a single call.

Course-correct if your issues are mainly scope and estimation. The product has value. The team is honest. The codebase works. Cut scope hard, switch to iterative budgeting, and demand evidence-based reporting. Timeline to stabilize: weeks, not months.

Intervene if you’re seeing process gaps and manageable debt on top of scope and estimation issues. Things work, but slowly. Status reporting is unreliable. Fix the Definition of Done, introduce CI/CD, get direct access to the team’s tools, and start paying down debt deliberately. Budget stabilizes once the bleeding points are plugged.

Question viability if you’re seeing faked progress, an empty codebase, no tests, or a Bus Factor of one. At this end of the spectrum, the question is no longer “how do we fix this” but “is this worth saving at all.” More budget without structural change just funds the same failure at a higher price.

Most overruns involve two or three patterns at once. When that happens, the severity of the worst pattern determines your action. Scope creep combined with honest estimation failures? Course-correct. Scope creep combined with faked progress? The trust and visibility problem is the dominant factor. You can’t course-correct what you can’t see. Let the most severe signal drive the decision.

The hardest part of this decision is the sunk cost fallacy. Everything already spent feels like a reason to keep going. It isn’t. The money is gone regardless. The only question that matters: given what you now know, would you start this project today in its current state? If the answer is no, continuing doesn’t protect your investment. It increases your loss.

What to Do When Your IT Project Is Over Budget

Where you go from here depends on what you saw in the sections above.

- “I need an honest baseline before I decide anything.” If this article helped you identify which patterns apply, the next step is quantifying the damage across your entire product. Our Product Health Checklist is a structured diagnostic covering Strategy, Discovery, Delivery, and Leadership — the same dimensions where the problems above take root. For a detailed walkthrough of the framework and what each pillar reveals: Is Your Product Secretly Sick?

- “Status looks green but nothing is truly shippable.” Our deep dive on the Watermelon Effect expands the seven red flags from this article into a full diagnostic, including how to build transparent “Kiwi” projects (green on the outside and inside) and what to do if you’re already in a watermelon situation.

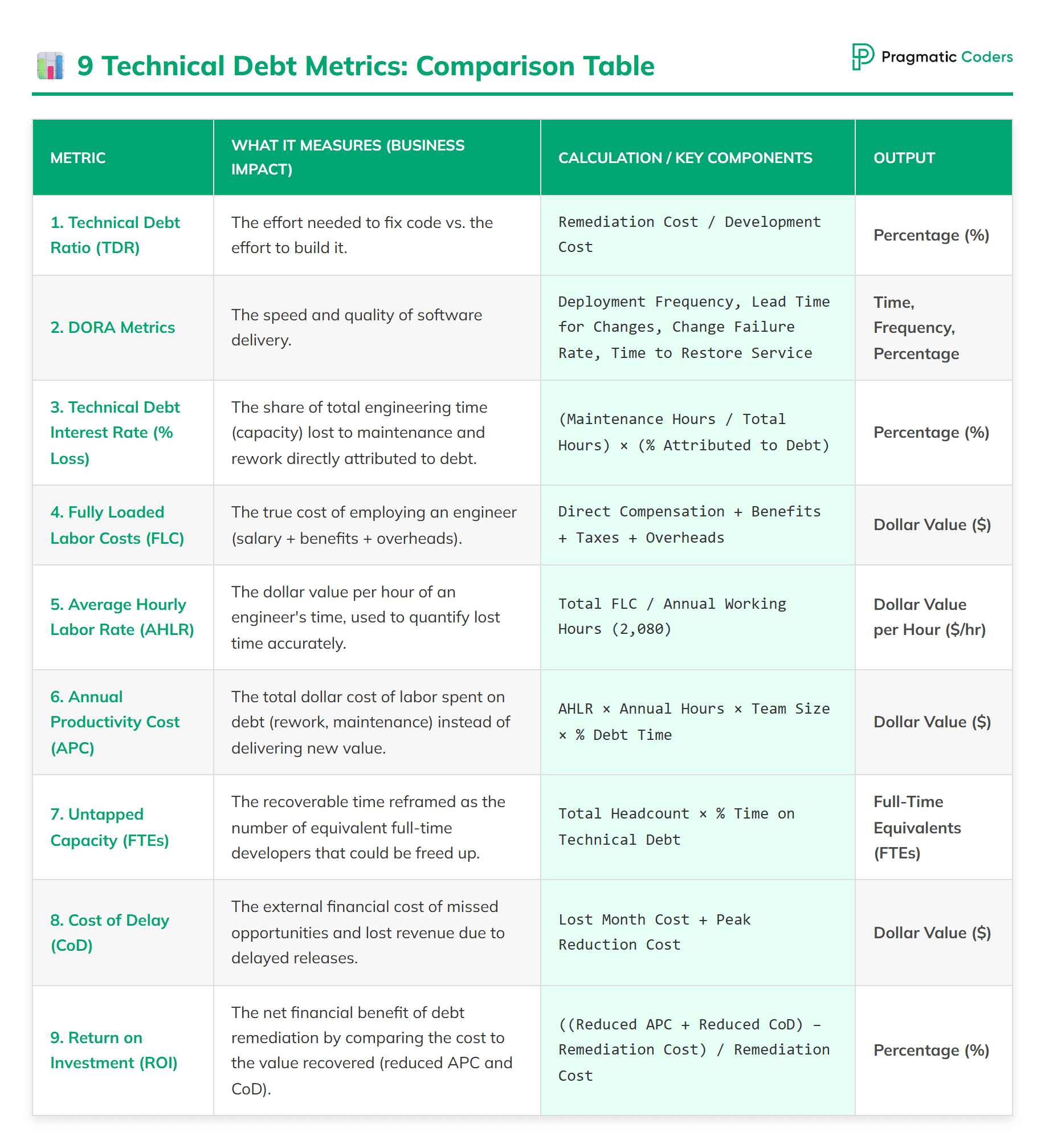

- “Technical debt is making every change expensive.” Our technical debt guide walks through how to classify debt by type, measure it with concrete metrics like cyclomatic complexity and test coverage, and prioritize fixes using a four-dimension framework. It’s the playbook for turning “everything is slow and we don’t know why” into a concrete repayment plan.

Conclusion

Budget overruns aren’t random. They follow patterns, each visible early if you know where to look.

These patterns don’t require malice. They just require the ordinary incentives and pressures of building software.

The most expensive decision in a struggling project isn’t adding budget. It’s adding budget without first understanding why the previous budget didn’t work. Diagnosis before dollars. Whatever the severity of your situation, the first step is the same: get an honest picture of where you actually stand before you make any irreversible decisions.