Hiring Consultants to Save Your Software Project? 5 Traps

Your software project is in trouble. It’s over budget, behind schedule, and the board is asking hard questions. Someone suggests bringing in consultants: Accenture, Deloitte, McKinsey Digital, or a boutique firm. It feels like the safe choice. A prestigious brand to reassure stakeholders. Expert methodology. Accountability you can point to if things go wrong.

Before you sign that statement of work, you need to understand something. Large consulting engagements, especially those structured around staff augmentation and time-based billing, have structural challenges that can undermine software rescue efforts. These challenges are built into how consulting engagements typically work. Understanding them helps you decide whether consulting is the right model for your situation, and if so, how to structure an engagement that actually succeeds.

Key Points

|

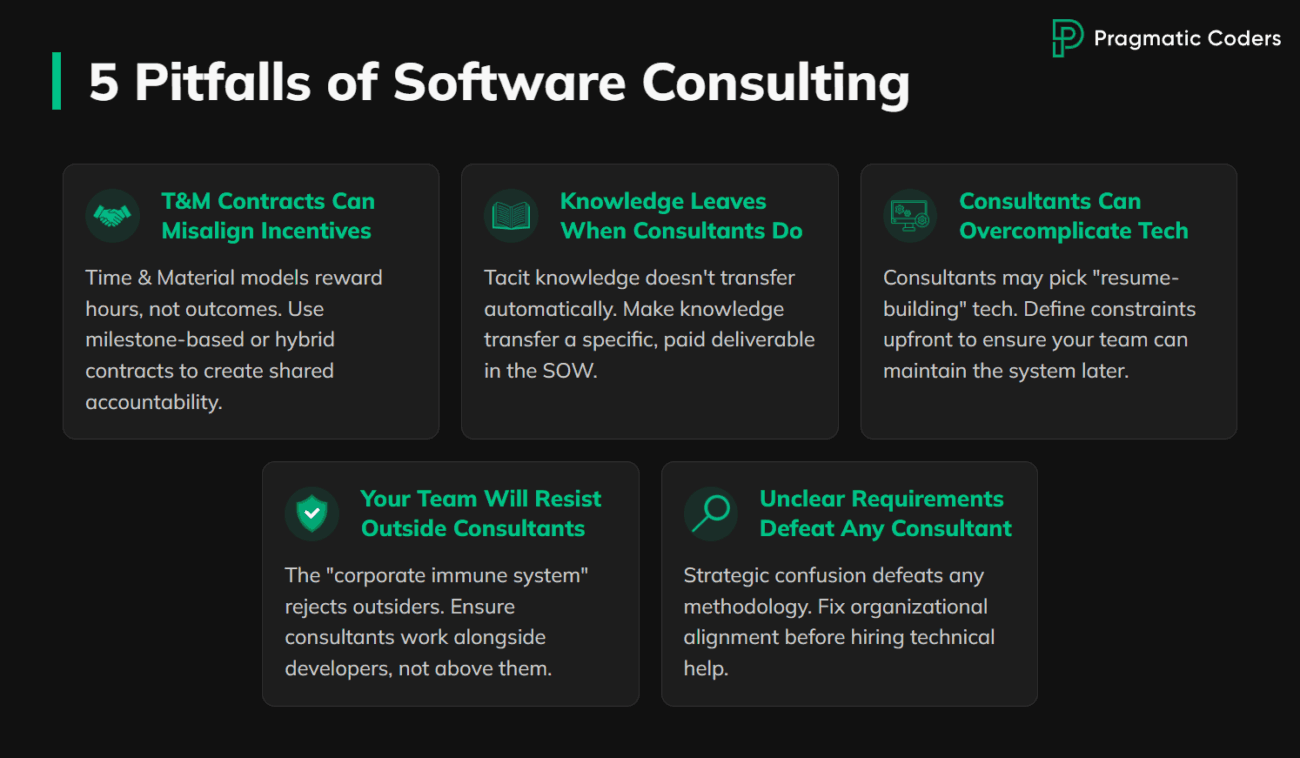

T&M Contracts Can Misalign Incentives

Standard T&M contracts create a structural gap between consultant success and client success. The consultant bills by the hour; your success depends on outcomes. The risk is asymmetric: if the project struggles, you absorb the business impact while billing continues. That’s the nature of the model, not a character flaw in consultants.

Rescue projects need decisive action and fast iteration. T&M doesn’t penalize slow progress the way fixed-price or milestone contracts do. Without intentional structuring, there’s no built-in pressure to prioritize speed over thoroughness.

To be fair, incentive misalignment runs both ways. Clients who delay decisions, change scope weekly, or withhold critical information also create conditions where rescues fail. A consultant absorbing constant uncertainty while the client avoids commitment is just as misaligned. Good engagements require accountability on both sides.

How to Structure Better Contracts

Negotiate milestone-based payments tied to deliverables, not hours worked. Your leverage is limited when you’re desperate, but if milestone-based terms aren’t even on the table, that tells you how the engagement will go. Boutique firms tend to be more flexible here than large consultancies with rigid contract structures.

That said, T&M exists for good reasons. Clients often choose it because they can’t define scope clearly enough for fixed-price, they want flexibility to pivot without renegotiating, or their procurement rules mandate it. The goal isn’t to eliminate T&M but to add accountability structures within it.

Hybrid models can work well: T&M for discovery phases where scope is uncertain, fixed-price for defined execution phases where deliverables are clear. This gives you flexibility early and accountability later.

Explore outcome-based bonuses in the SOW. These could be tied to launch dates, uptime targets, or other measurable outcomes. Penalties are harder to negotiate. Consultants will reasonably decline terms where the client can torpedo the outcome through slow approvals or scope changes. But a consultant who refuses any outcome-based upside is telling you something about how much ownership they’re willing to take.

If you can’t get milestones or outcome incentives, at minimum negotiate clear exit ramps. Regular checkpoints where you can adjust scope or exit without penalty give you control without requiring the consultant to accept unreasonable risk.

Knowledge Leaves When Consultants Do

In crisis mode, the default is “just fix it.” Without explicit design for knowledge transfer, consultants leave and your team is left with solutions they may not fully understand.

Tacit knowledge doesn’t transfer through documentation alone. The reasoning behind architectural decisions, the workarounds, the edge cases that took years to handle correctly – consultants take that context with them when they leave. And since most consultant incentive structures reward visible deliverables, knowledge transfer rarely happens unless you explicitly make it part of the scorecard.

The result is a maintenance gap. The rescue can work perfectly while consultants are on-site, then degrade once they leave. Your team may have the documentation but lack the intuition to troubleshoot or extend the system confidently.

How to Design for Knowledge Transfer

Make knowledge transfer an explicit, measurable deliverable in the SOW. Include acceptance criteria like “your engineer can deploy a change independently” or “your team can diagnose and fix a production issue without consultant support.”

Require embedded pairing, but tailor the approach to your situation:

- If you have an internal team: Pair consultants directly with your developers. This is the ideal scenario for knowledge transfer.

- If you’re working with an external vendor team: Ensure the consultant integrates with that team, not around them. The vendor’s developers need the knowledge too.

- If you have no team: Build knowledge transfer into the exit plan from day one. Who will maintain this? Hire or assign that person early so they can shadow the work.

Plan for a gradual transition, not an abrupt handoff. If the engagement is large enough, stagger consultant departure. Build in a post-handoff support period where consultants remain available for questions.

Consultants Can Overcomplicate Your Tech Stack

There can be a pull toward technologies consultants find professionally interesting. Without deliberate pushback, this can lead to choices that fit industry trends better than your team’s actual capabilities. Modern tech is genuinely exciting, and “best practice” often defaults to “what industry leaders use.” Individual consultants benefit professionally from working with architectures and tooling that look impressive on a resume, even when simpler alternatives would serve you better.

What works at Google-scale can be crushing for a company with 100-500 employees and a small dev team. If you have an in-house team, they may struggle to maintain systems built beyond their skill level. If you’re relying on external vendors, over-engineered architecture creates lock-in where you can’t easily switch providers. Either way, complex stacks require specialized talent and operational costs compound annually.

But sometimes “simpler” is what got you into trouble. The question isn’t simple vs. complex. It’s whether complexity is justified by your actual needs or by industry trends. A good consultant should articulate why a choice fits your capabilities and scale, not just why it’s a general best practice.

How to Keep Technology Choices Grounded

Define technology constraints upfront in the SOW: approved languages, frameworks, and infrastructure. Require written justification for any new technology introduction, including long-term maintenance implications.

Include “maintainability by your current team” as an explicit acceptance criterion. Ask the question directly: “Can our existing developers support this after you leave?” If the answer is “you’ll need to hire specialists,” challenge whether that complexity is necessary.

Consider requiring a technology review checkpoint before major architectural decisions are finalized. This gives you a chance to push back before commitments become expensive to reverse.

Your Team Will Resist Outside Consultants

Every organization has what consultants themselves call a “corporate immune system” – an instinct to protect existing processes and relationships. It’s such a well-known phenomenon that consultants warn clients about it because it derails engagements so often.

Without careful integration, consultant recommendations get diluted, delayed, or quietly ignored. The team has its own processes (whatever their quality), habits, and a culture that often reflects the broader company. External consultants are outsiders to that context, and the team may resist changes that threaten how they work – even when those changes would help.

Sometimes that resistance is correct. Bad advice should be resisted. But the defensive response doesn’t distinguish between good and bad interventions – it rejects both.

Common Resistance Patterns

Encapsulation happens when the team lets consultants work in isolation while continuing “business as usual” elsewhere. The consultant’s work becomes a parallel track that never merges with reality.

Assimilation is when new terminology gets adopted but practices remain unchanged. “Daily standups” become the same old status meetings where the manager dictates. The form exists without the function.

Exhaustion occurs when the team simply waits out the engagement. Responses come slowly, meetings get rescheduled, cooperation is minimal. The team knows consultants will eventually leave.

How to Build Real Integration

Start with selection. Large consultancies often send a polished sales team during selection and a different delivery team afterward. Ask to meet the actual people who will work on your project and get their names in the SOW. Check references specifically for rescue or turnaround engagements, not just greenfield builds.

Once the engagement starts:

- Ensure consultants work embedded with your team, not in a separate “consultant workstream.”

- Create direct channels between consultants and developers, not just management. If consultants only talk to executives, they’ll miss the ground truth your developers know.

- Announce the engagement transparently. Explain why you’re bringing in help and what success looks like. Surprises breed resentment.

Unclear Requirements Defeat Any Consultant

Methodologies, frameworks, and tools can solve technical problems. They can’t resolve strategic confusion. If your project is failing because requirements are contradictory, stakeholders disagree on priorities, or the market need is unclear, no consultant can fix that with better processes alone.

Fred Brooks identified this distinction in his 1986 essay “No Silver Bullet” as “essential” versus “accidental” complexity. “Accidental” complexity is fixable: bad tools, messy code, slow pipelines. Consultants are often excellent at this. “Essential” complexity is harder: confused business logic, undefined markets, misunderstood user needs. These require organizational alignment, not technical intervention. Brooks argued that essential complexity accounts for most of software’s difficulty, so even excellent process improvements address only the smaller portion. Consultants can optimize your tools and pipelines, but they can’t engineer their way out of unclear requirements.

The Limits of Heroic Intervention

When a project is in crisis, there’s a temptation to seek a “hero” who can work miracles. But if the project requires heroics to survive, that’s a symptom of deeper structural issues. A consultant can bail water, but they can’t plug a hole in the hull that nobody has agreed exists.

A consultant’s solution addresses the problem as understood at that moment. If the underlying requirements keep shifting or were never clear, the fix won’t stick.

How to Address the Real Problem First

Before signing a rescue engagement, diagnose whether your problem is primarily technical or organizational. If stakeholders can’t agree on what the product should do, no consultant will fix that – you need alignment first.

Run a short discovery phase to clarify requirements, priorities, and success criteria before committing to execution. Make sure consultants can get clear answers quickly – every day spent waiting for decisions is a day the rescue stalls.

Next Steps

Your next step depends on where you stand.

If T&M billing concerns you, learn when Fixed Price makes more sense. If you’re worried about technology choices creating lock-in, understand how to spot and prevent vendor lock-in before it’s too late.

If you’re wondering what a proper project takeover looks like, we’ve published a checklist for software project takeovers. If you’re not sure what’s actually broken, our product health checklist can help diagnose whether the problem is strategy, discovery, delivery, or leadership.

Before committing to any rescue approach, consider getting an independent audit to understand what’s actually broken and what your realistic options are.

Conclusion

Staff-augmentation and T&M-heavy consulting engagements have structural challenges: incentive alignment, knowledge transfer, technology choices, team integration, and problem diagnosis. These can undermine software rescue efforts if not addressed intentionally.

Hiring consultants can absolutely work for the right problems. Many consultants, especially experienced boutiques focused on outcomes, already address these challenges proactively. The goal isn’t to assume bad intent but to structure engagements so success doesn’t depend on luck in selection.

Before you sign that SOW, ask yourself three questions. Does this engagement create shared accountability for outcomes? Will my team be stronger after this, not just my codebase? Have we agreed on what’s actually broken?

If the answer to all three is yes, you’re set up for success. If not, fix those gaps before your next vendor conversation.