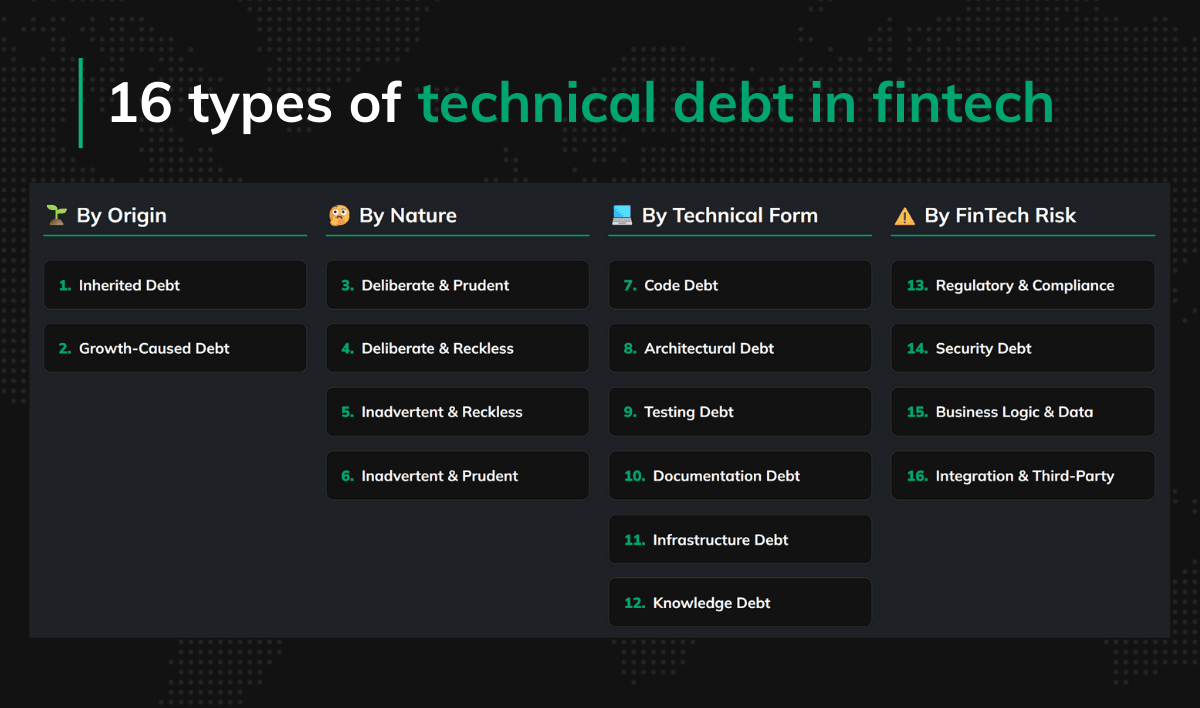

16 Types of Technical Debt in FinTech

Tech debt isn’t a one-size-fits-all mess. It shows up in different shapes depending on how old your codebase is, how fast your company moves, and how many shortcuts you’ve taken to hit deadlines. One team’s “quick fix” is another’s decade-long regret.

In the financial sector, you can see a few categories of debt tech. Some appear because your’re in the banking sector where legacy code is almost unavoidable (“inherited debt”) ); others rely on the debt’s form (code debt, architectural debt, etc.).

In this article, we go through various types of this debt in FinTech.

Our automation solution cut daily production incidents from 1.5 million to around 500 for a major e-commerce platform.

WebInterpret: Optimizing eCommerce Automation to Cut Incidents by 99.97%

What Is Technical Debt?

Technical debt = long-term costs from quick fixes, old code, and rushed decisions. It includes code, architecture, testing, and regulatory issues – all with financial and operational impact. Learn more about tech debt in FinTech in our previous article on why the debt can lead to a catastrophe, how much it costs, and most importantly, how to build a pragmatic strategy to manage it.

Check related articles:

- What is technical debt?

- How to find & manage technical debt

- Does AI make technical debt more expensive?

- From MVP to Scale-Up: The “Technical Debt” You Should Actually Keep

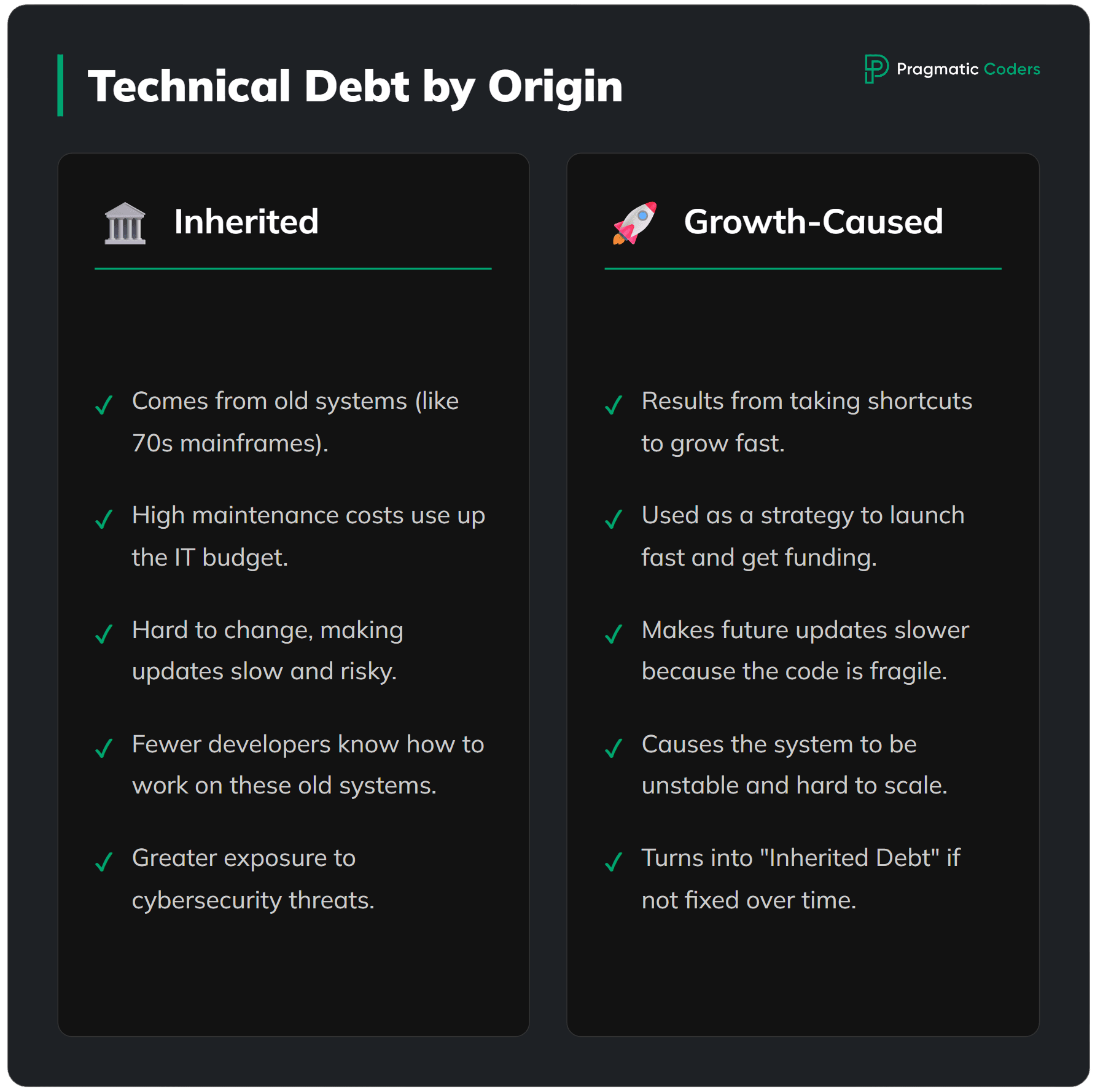

Tech Debt By Origin

This lens describes what the debt originated from.

1. “Inherited” Debt of Traditional Banking

Many global banks and financial institutions operate their core systems on architectures that date back to the 1970s and 1980s. These systems, typically built on mainframes using languages like COBOL, are classic examples of legacy debt. Everything’s packed into one tightly connected setup that used to work well – but now it just gets in the way of moving forward.

The impacts are broad and serious.

First off, maintaining these systems is incredibly expensive. Banks spend the majority – 70% – of their IT budgets on keeping outdated systems running.

Secondly, making any changes is a slow, risky, and costly process. Because there’s no modularity, changing one function can cause unexpected issues elsewhere in the system. This makes deployment take much longer, sometimes months or even years. It slows down time-to-market and makes them less competitive than faster companies.

Thirdly, banks are running into a growing skills gap. The people who know these old systems are retiring, and younger talent doesn’t want to work with outdated tech. This raises risks and pushes costs up. On top of that, legacy systems are more exposed to cyber threats because of old security and the challenge of adding modern protection. It’s a ticking time bomb, and one that’s hard to defuse at that. Modernization isn’t risk-free either, which makes weighing the pros and cons of a COBOL upgrade especially tricky.

We reduced the client’s technical debt and optimized the product backlog.We improved the development of Mulesoft’s flagship product.

2. “Growth-caused” Debt in FinTech

On the other end of the spectrum are fintech startups.

Unlike banks, they don’t have outdated systems. Their problem is the debt they take on to grow fast. To prove their model and get funding quickly, fintechs cut corners: they use basic but weak solutions, skip refactoring, do minimal testing, and neglect documentation. This “strategic debt” helps them launch fast.

But if this debt isn’t paid off, its “interest” grows fast. Development slows down. Even small features take time because the code is fragile and hard to change. The system becomes unstable, crashes more often, and hurts the user experience. As the user base grows, scalability issues appear and limit growth. What once helped the company start now holds it back.

Tech debt follows a company’s growth:

- In the startup phase, it’s a survival tool.

- In the scale-up phase, if unpaid, it slows progress and raises costs. At this point, the company must choose to reduce it.

- If not, in maturity, the debt hardens into “inherited debt,” leaving the company open to disruption, just like traditional banks.

Knowing where you are in this cycle helps you decide when to take on debt and when to start paying it down.

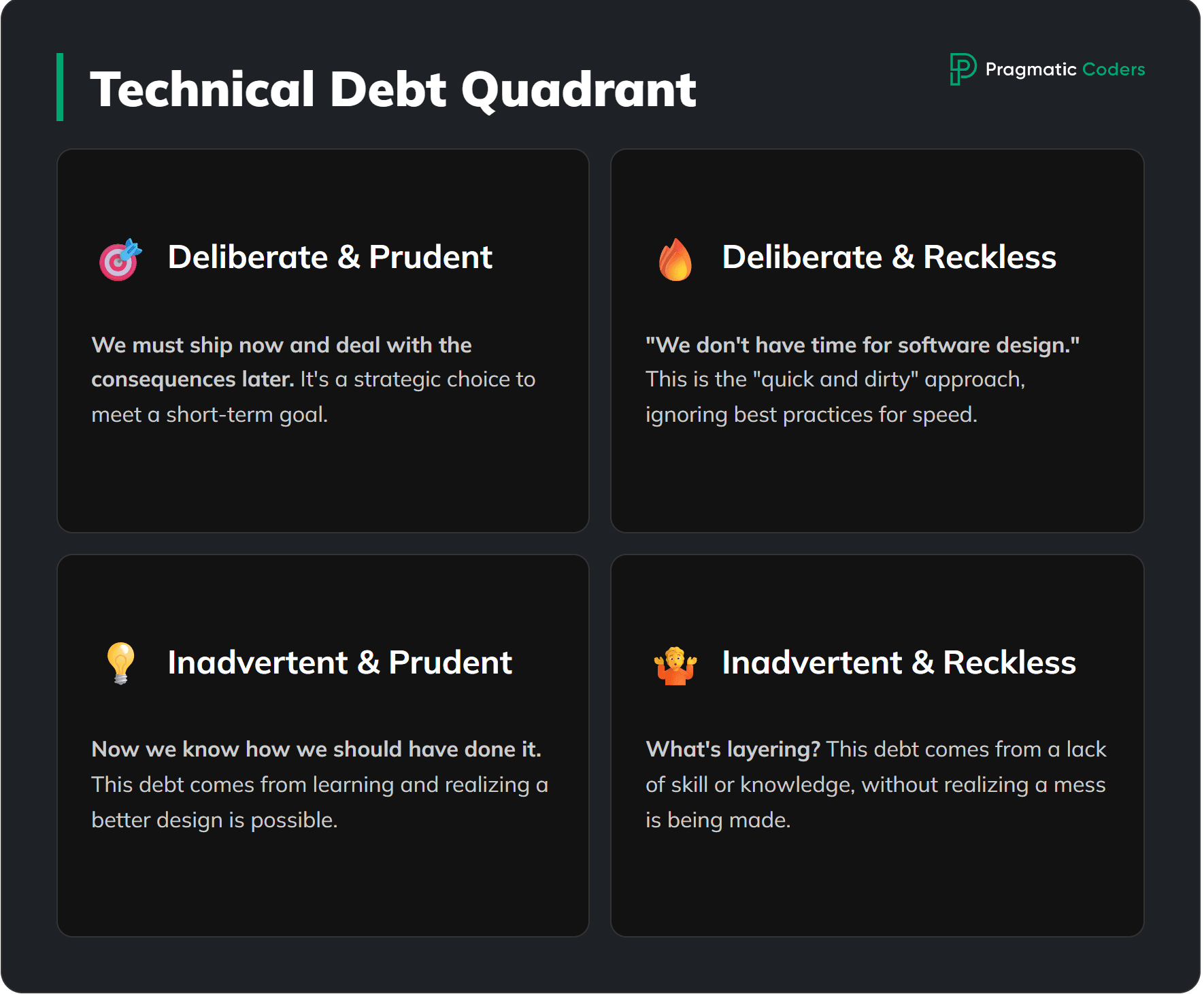

Tech Debt By Nature

Cunningham introduced the metaphor, but Martin Fowler refined it with his “Technical Debt Quadrant”. This model classifies debt as deliberate or inadvertent, and prudent or reckless, giving a clearer way to discuss the causes and types of design flaws.

3. Deliberate and Prudent

This is strategic technical debt: a deliberate choice to trade quality for speed to meet a short-term goal. For example, a startup might rush an MVP to secure funding. The team knows the trade-offs, accepts the future cost, and plans to fix it later. It’s treated as an investment.

4. Deliberate and Reckless

This quadrant covers debt taken on knowingly but without a solid reason. It’s the “quick and dirty” approach – ignoring best practices under pressure for speed, often from tight deadlines or poor culture. Teams here usually fail to see how fast the long-term cost will outweigh the short-term gain.

5. Inadvertent and Reckless

This debt comes from lack of skill or knowledge. The development team produces a low-quality, messy codebase without even realizing it. They are not making a strategic trade-off; they simply lack the skills or knowledge to produce a better design. It’s one of the riskiest types because the team doesn’t realize the damage being done.

6. Inadvertent and Prudent

This is the most subtle form of debt. Even skilled, disciplined teams accumulate it over time. As a team works on a complex system over time, their understanding of the problem domain deepens. After months or even years, they may realize that their initial, well-considered design is no longer optimal given their new, hard-won knowledge. This kind of inadvertent debt comes from growth in understanding, not negligence. It’s the type Cunningham meant: debt from learning.

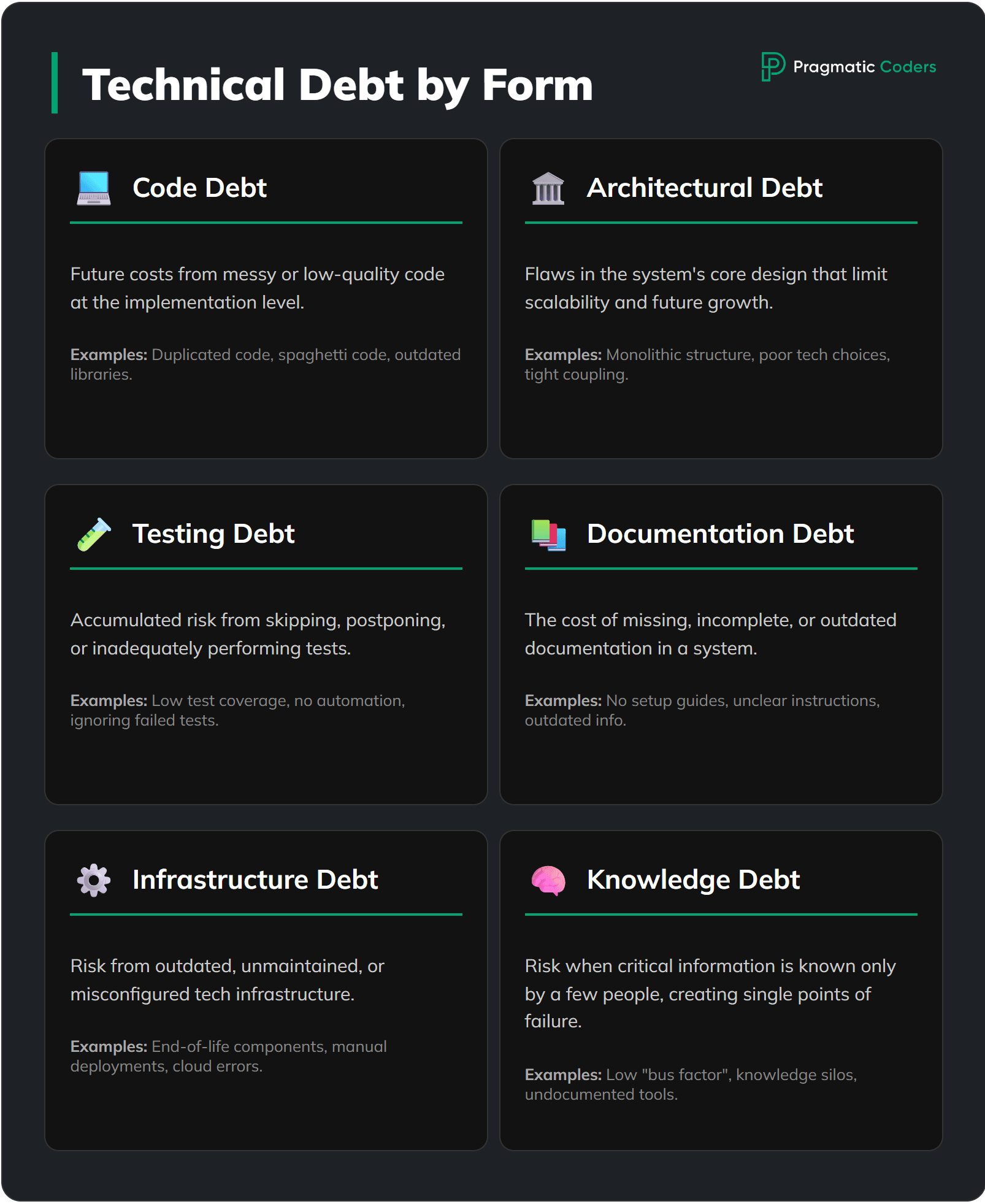

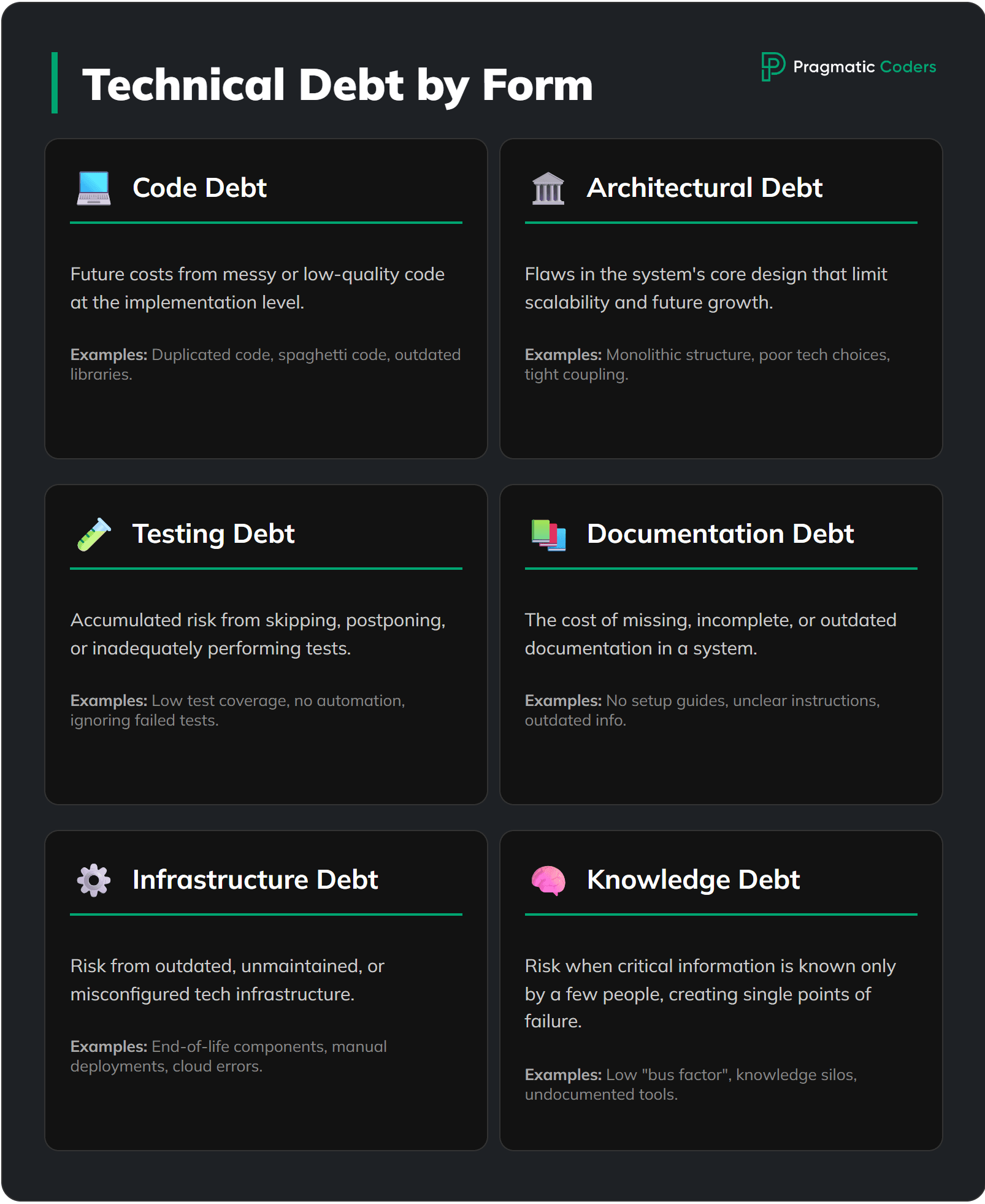

Tech Debt By Technical Form

To manage tech debt effectively, we need a common language to categorize its different forms. Here are a few:

7. Code Debt

Code Debt, often used interchangeably with the broader term “technical debt,” refers specifically to the future costs implied by suboptimal decisions made at the source code implementation level. It is the most granular and tangible form of debt, manifesting directly within the codebase through recognizable patterns and anti-patterns.

Examples: duplicated code, hardcoded values, “spaghetti code’, outdated libraries.

8. Architectural Debt

Architectural debt results from flawed decisions in the foundational design and structure of a software system, which can limit scalability, flexibility, and long-term stability.

Examples: monolithic structure, poor technology choices, ignoring non-functional requirements, tightly coupled components.

9. Testing Debt

This type of debt refers to accumulated risk from postponing, compromising, or inadequately executing testing activities, which leads to a higher likelihood of bugs in production.

Examples: insufficient test coverage, lack of automated testing, ignoring failing tests, skipping non-functional tests.

10. Documentation Debt

Documentation Debt is the cost of missing, incomplete, or poor documentation in a software system. Though often treated as less important than writing code, neglecting documentation slows teams down, makes systems harder to maintain, and limits growth. It also leads to Knowledge Debt, since it fails to turn short-term knowledge in developers’ heads into clear, lasting information others can use.

11. Infrastructure Debt

Infrastructure Debt is the risk from outdated, unmaintained, or misconfigured tech infrastructure. It can weaken the stability, security, and performance of all systems that rely on it.

Examples: End-of-life (EoL) components, delayed upgrades, manual deployments, misconfigured cloud resources.

12. Knowledge Debt

Knowledge Debt is the risk when key information lives only in a few people’s heads, creating single points of failure. It’s often measured by the “bus factor”: how many people can leave before the team loses critical knowledge.

Examples:

- Low “Bus Factor”: A project is at risk if a single key person leaves because only they understand a critical part of the system

- Knowledge Silos: Information is trapped within specific individuals or small groups.

- “Haunted Graveyards”: Parts of the codebase that were written by someone who has long since left the company. No one on the current team fully understands how they work, so they are afraid to modify them.

- “Shadow IT”: Critical tools or processes are created and used by a department but are undocumented and unsupported by the central IT organization, with their operation known only to a handful of people.

Tech Debt By FinTech-Specific Business Risk

Most software companies face common types of debt, but in finance (where regulation, security, and money are central) unique forms appear. Here, understanding debt isn’t just about efficiency, but about survival.

13. Regulatory and Compliance Debt

This is likely the most critical type of debt in FinTech. It happens when a system is built without fully considering current or future regulations.

- Causes:

- Launching in a new market without fully applying its financial rules, like reporting standards or credit laws.

- Treating KYC and AML checks as an afterthought instead of a core part of the user onboarding and transaction monitoring architecture.

- Using temporary fixes or hardcoded logic to meet data and AI regulations for protecting individuals (like GDPR. CCPA, or recent Genius Act) which makes it difficult to adapt in the future.

- Delaying implementation of regulatory reporting frameworks required by bodies like the SEC, FCA, or ESMA.

- Consequences: The cost of this debt isn’t just slower development. It can lead to major fines, license suspensions, and severe reputational damage. For 2024, Fenergo reported that global regulators issued a total of $4.6 billion in enforcement actions for AML and sanctions violations. This debt can shut a company down overnight.

14. Security Debt

All tech companies face security risks, but for FinTechs it’s an existential threat. Security debt builds up when speed is chosen over strong security.

- Causes:

- Skipping or rushing security code reviews and penetration tests to hit a launch deadline.

- Using outdated encryption or mismanaging cryptographic keys.

- Using weak authentication and authorization (e.g. missing multi-factor checks for critical actions).

- Storing sensitive data like secrets or API keys in insecure locations.

- Consequences: The impact is direct: stolen funds, major data breaches, and lost customer trust. In 2025, the average breach cost in finance was $5.97 million per IBM.

We rewrote legacy code to meet SEC compliance standards and secure the platform’s future scalability.

We made this app SEC-compliant

15. Business Logic & Data Integrity Debt

This debt arises from implementing complex financial calculations, business rules, or transaction ledgers in a way that is opaque, difficult to verify, and brittle. In finance, a rounding error isn’t a minor bug—it’s a financial loss.

This debt comes from building complex financial calculations, business rules, or transaction ledgers in a way that’s hard to verify and prone to breaking. In finance, even a rounding error means real losses.

- Causes:

- Hardcoding interest, fees, or currency conversions with “magic numbers” and unverified formulas, without documentation or tests.

- Missing a clear, unchangeable audit trail for transactions, so reconciliation hard or impossible.

- Using inappropriate data types for financial calculations (e.g., using floating-point numbers instead of fixed-point decimals for currency, which can lead to rounding errors).

- Consequences: This debt causes wrong balances, customer disputes, financial losses, and failed audits. It weakens the product’s core function and trust.

16. Integration and Third-Party Debt

The modern FinTech ecosystem is built on APIs. Companies rely on third parties for payment processing (Stripe, Adyen), identity verification (Veriff, Onfido), market data feeds, and connections to legacy banking infrastructure (Plaid). This dependency creates its own form of debt.

- Causes:

- Tightly coupling core logic to a specific provider’s API vendor changes hard later.

- Not adding resilience like circuit breakers or fallbacks for when a third-party service is down.

- Not version-locking APIs or planning for deprecations and breaking changes from partners.

- Consequences: An outage at a key provider can shut down the whole platform. Vendor lock-in limits flexibility if costs rise or needs change. This debt hands part of your platform’s stability and future to someone else.

Conclusion

Technical debt in FinTech is a business risk, not just a coding problem. Whether from legacy systems or fast startup growth, it has long-term effects.

By breaking down debt by source, intent, form, and risk, companies can assess, prioritize, and plan better.

Work with us. We’ve rescued many legacy codebases (for Mulesoft, WebInterpret, and more) and turned technical debt into stable, scalable systems. Let’s do the same for you.

Do different categories of technical debt overlap?

Yes. Categories of technical debt often overlap. For example, a Growth-Caused Debt in a FinTech startup may also appear as Code Debt or Testing Debt, and eventually lead to Regulatory Debt. Viewing debt from multiple perspectives helps companies identify, prioritize, and manage their overall debt portfolio more effectively.

What are the main types of technical debt in banking and FinTech?

Inherited Debt: Legacy systems in banks, often COBOL-based, that are costly and hard to maintain.

Growth-Caused Debt: Startup shortcuts for speed that later limit scalability.

By Intent: Strategic (deliberate) vs accidental (inadvertent) debt.

By Form: Code, architecture, testing, documentation, infrastructure, and knowledge debt.

By Risk: Regulatory, security, data integrity, and integration-related debt.

Why is regulatory debt critical in FinTech?

Regulatory debt occurs when financial systems don’t fully comply with regulations like KYC, AML, GDPR, or SEC reporting. The consequences go beyond slower development — they can include multimillion-dollar fines, loss of licenses, and reputational damage.

How can FinTech companies reduce technical debt?

Regularly refactor and modernize legacy code.

Invest in automated testing and documentation.

Prioritize compliance from day one.

Monitor third-party integrations and avoid vendor lock-in.

Treat technical debt as a measurable part of business risk.