Why Hiring 10 More People Won’t Solve Your Speed Problem

Adding more people doesn’t always speed things up – just like more cars in traffic slow it down. In scale-ups, the real issue is often system friction: onboarding, dependencies, meetings, context switching, and overloaded seniors.

Paradoxically, the biggest speed gains often don’t come from hiring, but from removing bottlenecks.

In this article, I explain why ‘just hire 10 more devs’ rarely solves speed problems in scale-ups, and the six questions you should ask before increasing headcount.

|

Why “More People” Doesn’t Mean “More Speed”

Onboarding Has a Real Cost (and Someone Has to Pay It)

In theory, it’s simple: more people = more work done in the same time. In practice, when a company has found product-market fit and is growing, a second component enters the equation: coordination. New people need to be onboarded, synchronized, introduced to the domain and decision-making processes. This doesn’t happen “for free” – the cost is usually borne by the best people in the organization, exactly those whose time is already most constrained.

Frederick Brooks described this phenomenon in his seminal 1970s book The Mythical Man-Month, formulating what’s known as Brooks’s Law: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” Why? Because new team members not only don’t deliver value from day one, they actually slow down the team through the need for training, context explanation, and answering questions. Brooks estimated that a new programmer’s true productivity in the first months can even be negative—they take more time from experienced team members than they deliver themselves.

Someone needs to be their mentor, code reviewer, answer questions about architecture, processes, and business context. That “someone” is usually your best seniors—the ones whose time is most critical to the project.

Communication Grows Faster Than the Team

On top of that comes a phenomenon that managers feel intuitively: as the team size grows, so does the number of interactions, alignments, and dependencies. If work isn’t well divided into independent areas, the team starts waiting instead of accelerating: for decisions, for feedback, for approvals, for “someone with context.” Then “adding people” increases the queue, not throughput.

Brooks observed that the number of potential communication channels in a team grows according to the formula n(n-1)/2, where n is the number of people. This means:

- A 5-person team has 10 communication channels

- A 10-person team has 45 channels

- A 20-person team has 190 channels

This isn’t linear growth—it’s a complexity explosion. And each communication channel is a potential meeting, synchronization, email, Slack message, review, or decision to be made.

Dependencies Between People Create Queues, Not Speed

When a team grows without clear division of responsibilities and autonomy, inter-personal dependencies emerge. Developer A waits for a review from B, who waits for a decision from C, who waits for input from D. Each such dependency is a queue. And queueing theory (used in production flow management, among other things) is clear: waiting time grows exponentially with resource utilization.

In other words: the more overloaded your key people are (tech leads, architects, product managers), the longer everyone else waits for them. And adding another 10 people… just increases the number of people waiting in the queue.

Three Mechanisms That Slow Down Scale-Ups in Practice

Context Switching Eats the Day (Especially for Leaders and Seniors)

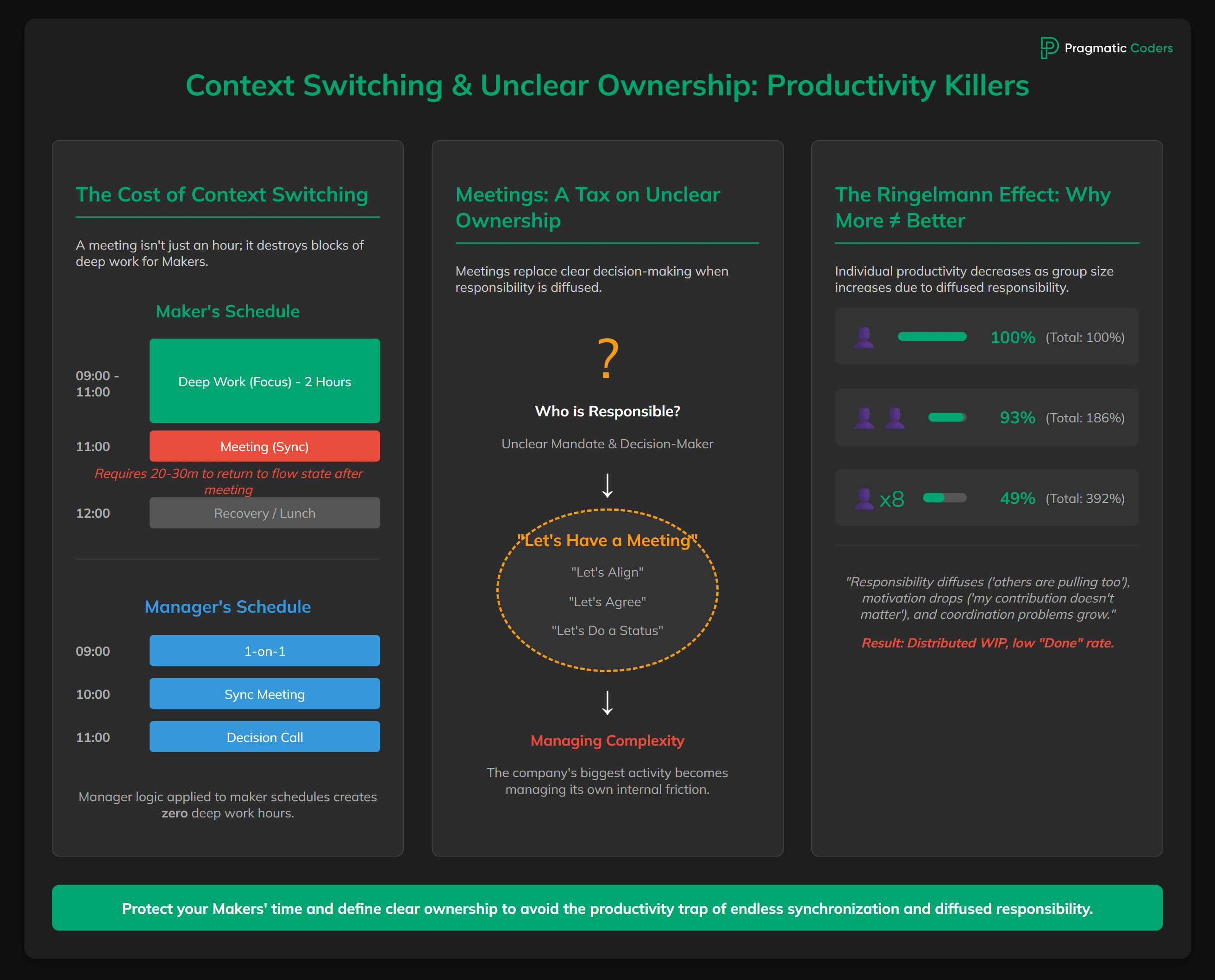

The most underestimated speed killer is context switching. For people who create (engineers, product, design), a day chopped up by meetings isn’t “slightly less productive.” It ceases to be a working day, because work requiring focus needs blocks of time. If intensive onboarding of new people is added to this, the calendars of key people become minefields: every hour “helping” is subtracted from work that actually moves the initiative forward.

Paul Graham in his essay Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule describes the fundamental conflict between two types of work schedules:

- Manager’s Schedule: day divided into hour-long slots, meetings, synchronizations, decisions. Natural for C-level and middle management.

- Maker’s Schedule: work requiring long, uninterrupted blocks of time (minimum 3-4 hours) for deep concentration. Natural for engineers, designers, analysts.

The problem appears when we apply manager logic to a maker’s schedule. A meeting at 11:00 AM isn’t just “one lost hour”—it’s a destroyed entire morning block. A programmer knows they only have 1.5 hours before the meeting, so they don’t start a complex task. Then after the meeting, they need 20-30 minutes to return to a “flow state.” The result? A day with meetings at 11:00 and 14:00 yields practically zero hours of deep work.

Meetings Are a Tax on Unclear Ownership

Meetings often aren’t the problem themselves. The problem is that they replace ownership. When it’s unclear who makes the decision, who has the mandate to cut scope, and who bears responsibility for the outcome, the organization automatically enters synchronization mode: “let’s align,” “let’s agree,” “let’s do a status.” At some point, the company’s biggest activity becomes managing its own complexity.

“Everyone Does Everything” Ends with Nobody Delivering

Another slowing mechanism is lack of clear division of responsibilities. When there’s no clear ownership (“this is yours, you’re responsible for the outcome”), the organization starts operating in a “collective responsibility” model. Which sounds beautiful in theory, but in practice ends with distributed WIP (Work In Progress).

Everyone does a bit in many projects. Nobody has full context. Nobody feels 100% responsible for delivery. The result? High number of things “in progress,” low number of things “done.”

That’s the Ringelmann Effect—a phenomenon first described by Maximilien Ringelmann and popularized by Walther Moede’s 1927 summary – shows that individual productivity decreases as group size increases. In a rope-pulling experiment:

- 1 person gives 100% of their strength

- 2 people give an average of 93% each (total 186%)

- 8 people give an average of 49% each (total 392%, not 800%)

Why? Because responsibility diffuses (“others are pulling too”), motivation drops (“my contribution doesn’t matter anyway”), and coordination problems grow.

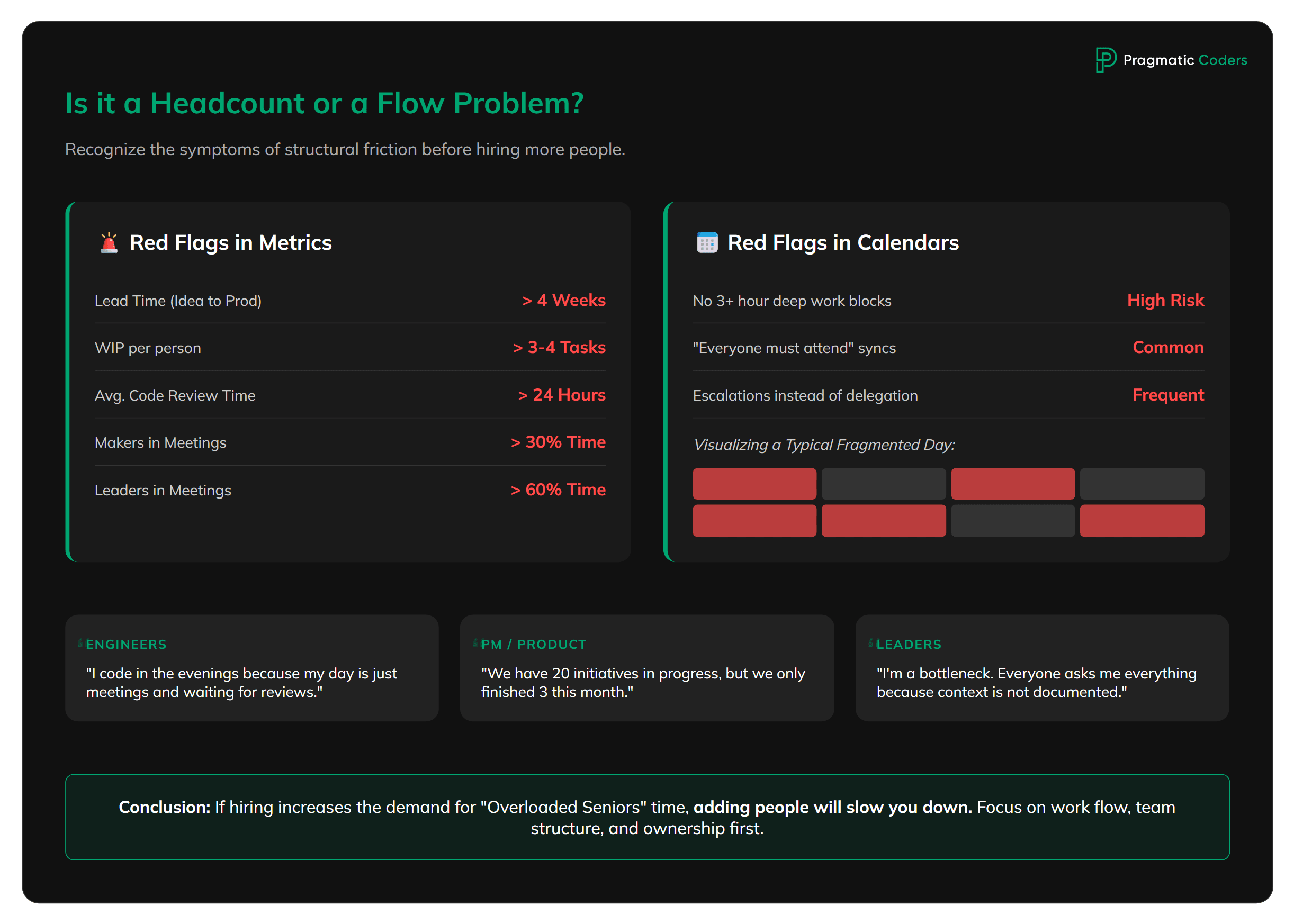

How to Recognize That the Problem Isn’t Headcount

Symptoms in Metrics and Calendars

If frustration is growing in the organization that “we’re doing a lot but delivering little,” it’s often not a headcount problem. It’s a flow problem. Symptoms are surprisingly repetitive: long lead times (time from idea to deployment), high number of items “in progress,” frequent blockers between teams, and leaders’ calendars full of meetings where “everyone must be there.”

Red flags in metrics:

- Lead time > 4 weeks for basic features (from decision to production)

- WIP per person > 3-4 active tasks simultaneously

- Code review time > 24h on average

- % time in meetings > 30% for makers (developers, designers)

- % time in meetings > 60% for technical leaders

Red flags in calendars:

- No 3+ hour blocks without meetings during the week

- Meetings “everyone from the team must attend”

- Weekly “quick alignments” that last 1-2 hours

- Decision escalations “upward” instead of delegation “downward”

Typical Signals from the Organization (That You’ll Hear from PMs and Engineers)

The second signal is “overloaded seniors.” If simultaneously: (1) the number of new people is growing, (2) the number of initiatives is growing, (3) the number of dependencies is growing, and (4) key decisions and reviews flow to a narrow group, then a bottleneck naturally forms. And here hiring can even worsen the situation—because it increases demand for the same seniors’ time.

Typical statements indicating a structural problem, not a headcount one:

From engineers:

- “I can’t start because I’m waiting for review/decision/feedback”

- “Half the day goes to meetings, I code in the evenings”

- “I don’t know who’s responsible for X, so I organized a meeting with 8 people”

From PM/Product:

- “We have 20 initiatives in Q, but we’re delivering 3”

- “Devs say they’re busy, but I don’t see progress”

- “Every decision requires 5 meetings and 10 people”

From leaders:

- “90% of my time is onboarding, reviews, and meetings. When do I code/design?”

- “People ask me about everything because nobody else has context”

If you hear any of the above—the problem isn’t in the number of people, but in work flow, team structure, and ownership.

What to Do Instead of “Let’s Hire 10 People”

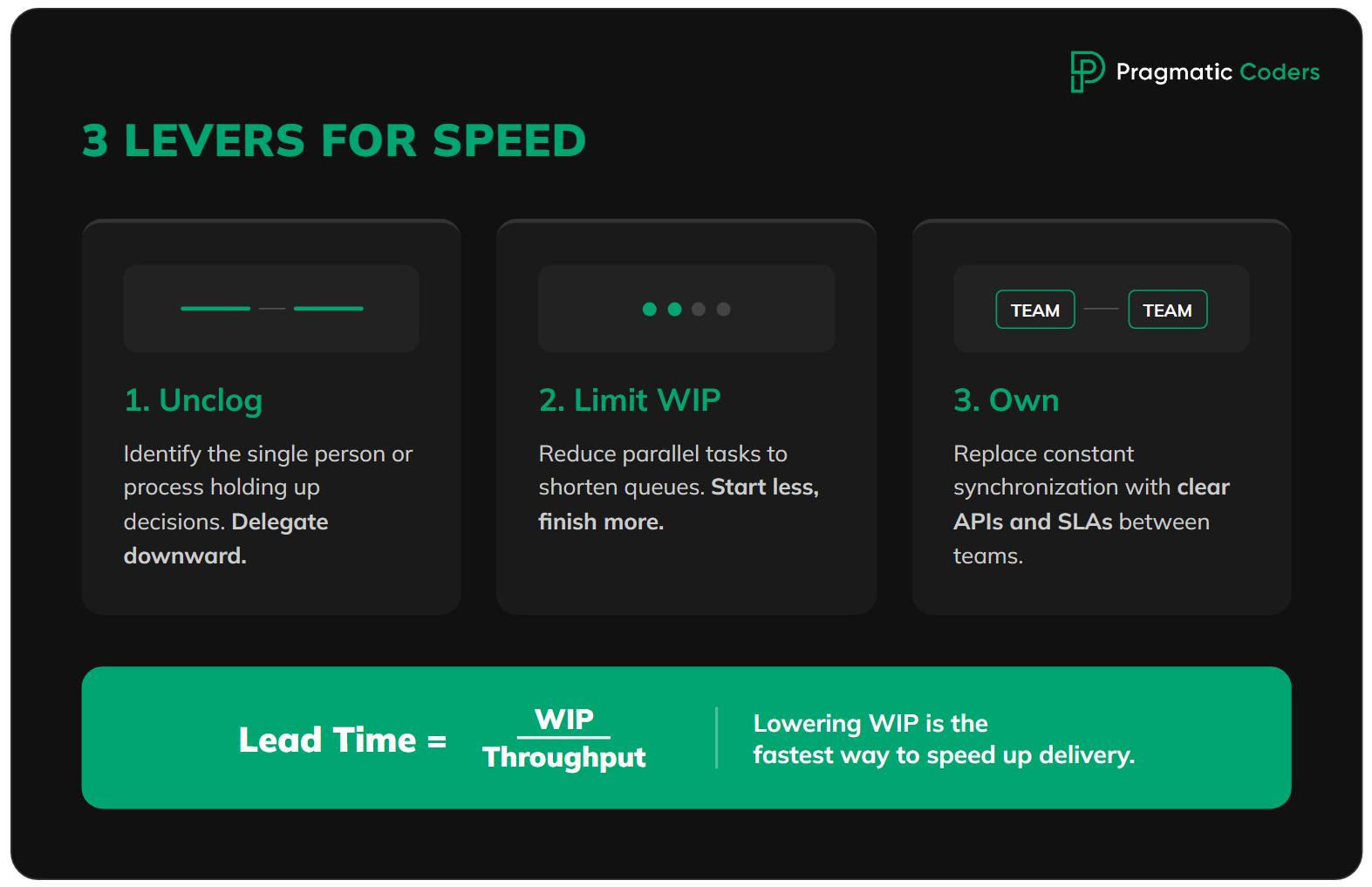

First Unclog the Bottleneck (Usually Seniors / Review / Decisions)

Before you increase headcount, identify the one bottleneck that actually limits speed. In scale-ups, it’s often: decisions (who decides), review/approvals (who gives the green light), or “knowledge in heads” (who has context). If you don’t unclog this spot, new people will only increase pressure on an already overloaded point.

Practical steps:

Value stream mapping—literally draw how work flows from idea to production. Where’s the longest queue? Where do people wait?

Delegate decisions downward—instead of escalating everything to tech lead/CTO, define frameworks and delegate decisions. Example: “Product owner can cut scope to 80% of original plan without escalation.”

Asynchronous review—instead of waiting for synchronous review meetings, introduce written decisions (ADR – Architecture Decision Records, RFC – Request for Comments) with a feedback deadline.

Context documentation—if the only person who knows system X is a senior dev, invest 2 weeks in documentation and knowledge transfer. Short-term slowdown, long-term bottleneck unlocking.

Example from practice: One project described in Rapid Development had a problem: every deployment required lead architect approval, which happened once a week (Fridays, 4:00 PM). Result? Queue of 15-20 changes waiting for deployment. Solution? Automated integration tests + self-service deployment with rollback. Lead architect moved from “approve every change” to “review incidents once a week.” Deployment frequency: from 1x/week to 10x/day.

Limit WIP and Shorten Queues (Start Less, Finish More)

The second lever is simple but culturally difficult: start less, finish more. Limiting the number of parallel items and ordering priorities usually gives quick results because it shortens queues and reduces the number of synchronizations. It doesn’t sound like a “spectacular transformation,” but often gives the fastest return because it reduces friction in the work system.

Queueing theory (used in Lean and Kanban) is clear: The higher the WIP, the longer the completion time.

Little’s Law: Lead Time = WIP / Throughput

Where:

- Lead Time = time from start to completion of a task

- WIP = number of tasks in progress

- Throughput = number of tasks completed per time unit

If you have WIP = 30 tasks, and you complete 10/week, average lead time = 3 weeks. If you cut WIP to 15, with the same throughput, lead time drops to 1.5 weeks.

Practical WIP limits:

- Per person: maximum 2-3 active tasks (1 main + 1-2 supporting/reviewer)

- Per team: number of active initiatives ≤ number of people on team

- For organization: track WIP at epic/project level, not just tasks

Define Ownership and Collaboration Interfaces (To Reduce Synchronizations)

The third lever: clear division of responsibilities. If every feature requires synchronization of 3 teams, don’t add more teams. Change the structure so each team can deliver value end-to-end in their area.

Inspiration: Team Topologies (Matthew Skelton, Manuel Pais) describes 4 team types:

- Stream-aligned team—responsible for a specific business value stream (e.g., user onboarding, payments)

- Platform team—provides tools and infrastructure as an internal service

- Enabling team—helps other teams develop competencies

- Complicated subsystem team—handles specialized area (e.g., ML, search engine)

Key principle: most work should be done within one team, without constant inter-team dependencies.

When you have clear boundaries and interfaces (APIs, contracts, SLAs), teams can work autonomously. Number of meetings, synchronizations, escalations drops. Speed increases.

When Hiring Actually Accelerates

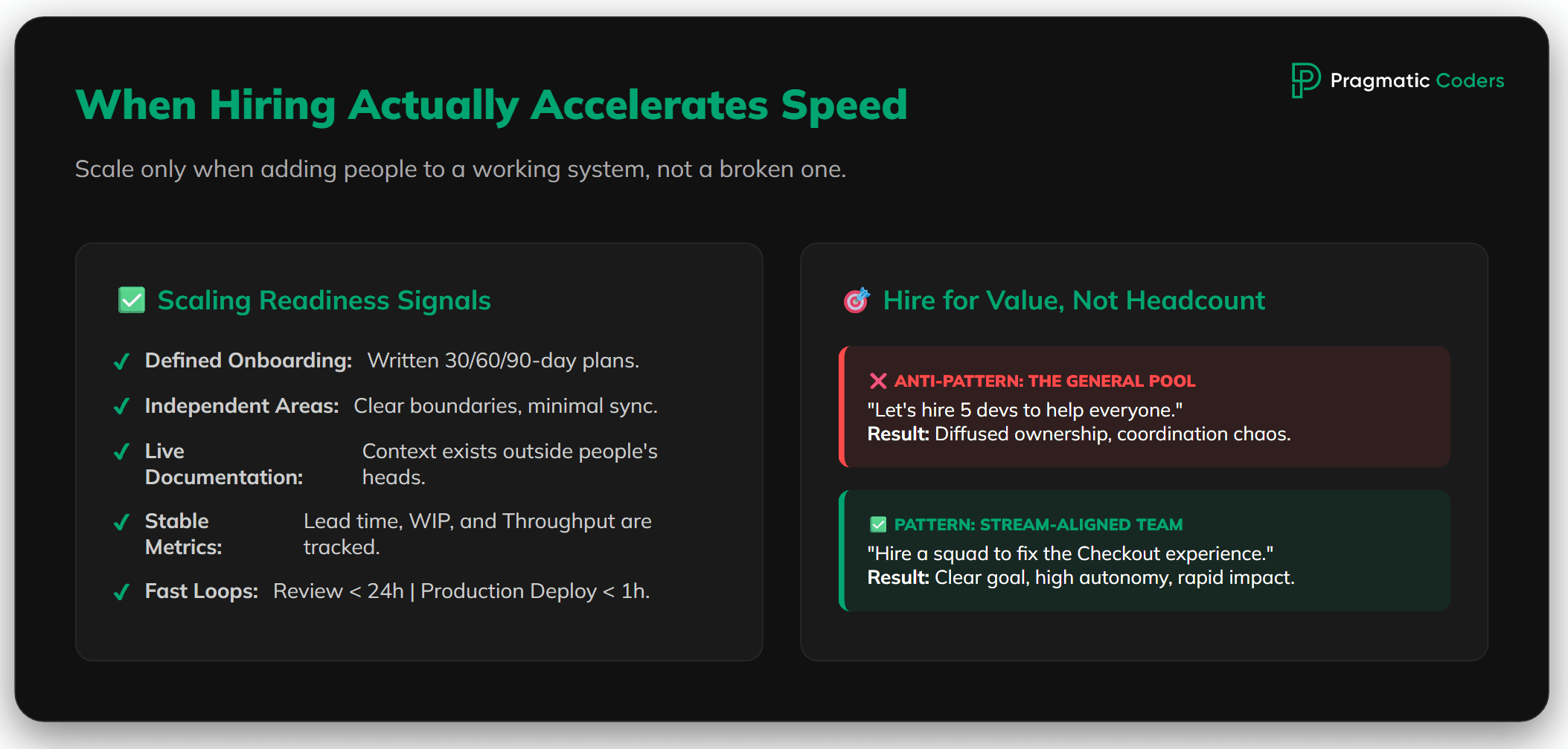

When You Have a “Ready Work System” and a Place Where New People Immediately Add Value

Hiring works when the organization has a prepared “onboarding track”: clear division of responsibilities, sensible onboarding, documented decisions, and a stable delivery rhythm. Then a new person doesn’t mainly generate questions and meetings, but quickly takes over a specific area. In other words: headcount accelerates when we add people to a working machine, not to a machine that still needs to be assembled.

Signs that the organization is ready for team scaling:

✅ Defined onboarding: new person has a written plan for first 30/60/90 days, knows their mentor, has a list of onboarding tasks

✅ Independent areas: there are clear responsibility boundaries, minimal inter-team dependencies

✅ Documentation: architecture, decisions, processes are written down (not just “in heads”)

✅ Stable processes: code review in <24h, production deploy in <1h, incidents have playbooks

✅ Metrics work: team measures lead time, WIP, throughput and sees trends

If most of the above are ❌—first build the work system. Only then scale.

When You’re Hiring for a Specific Value Stream, Not for a “General Pool”

Hiring works when you know exactly what the new person will do and how to measure their impact. The worst model is “let’s hire 10 devs for the pool, they’ll distribute somehow.”

Anti-pattern: “We need more frontend devs. We’re hiring 5. Let them split between teams X, Y, Z.”

Result? No clear ownership, each person works on 3 projects, nobody feels responsibility for the outcome, communication explodes.

Good practice: “We’re establishing a new stream-aligned team responsible for checkout & payments. We need 1 tech lead + 4 mid/senior devs (2 BE, 2 FE). Goal: shorten time from ‘add to cart’ to ‘payment confirmation’ from 8 to 3 steps in Q3.”

Result? Clear goal, clear team, clear responsibility. New people know “why they’re here.”

Pattern from Pragmatic Coders: Instead of building a large in-house team that needs to be scaled through trial and error, many scale-ups opt for a hybrid approach: a stable core responsible for strategy and ownership + a flexible team extending capacity. The key isn’t “adding people without a system,” but entering a ready, working ecosystem where the new team has defined scope, collaboration interfaces, and a way to measure success.

This model allows scaling without multiplying meetings and dependencies—provided there’s a clear division: who makes decisions, who delivers value, who integrates the result.

Quick Checklist for C-Level and Head of Eng

Before you approve the next headcount, go through this list:

What’s today’s main bottleneck: decisions, review, knowledge, dependencies, or priorities? → If you don’t know, map the work flow (value stream mapping). New people won’t help if the bottleneck isn’t in “hands to work.”

Who will onboard and how much time will it take in the first 4-8 weeks? → If your seniors already don’t have time for deep work, adding onboarding can completely disable them from productive work.

How many items are “in progress” per person/team and can we limit this? → If WIP per person > 3, the problem isn’t headcount, but flow management. First limit WIP.

Do we have clear ownership (who delivers the outcome, not “participates”)? → If the answer is “teams X, Y, and Z jointly responsible,” the actual meaning is “nobody’s responsible.” First define ownership.

Do key people’s calendars have blocks for deep work, or are they chopped up? → If tech lead / senior dev has <50% of the week for deep work, there’s nobody to mentor new people or do critical technical work. First unblock calendars.

How will we verify in 30 days whether we’ve actually accelerated? → If you don’t have an answer, don’t hire. A good answer is a specific metric: “Lead time will drop from 4 to 2 weeks” or “Deployment frequency will increase from 1x/week to 1x/day.”

What to Measure After 30 Days to Know If It Worked

Success metrics when increasing the team (or optimizing without increasing):

| Metric | Before | Target after 30 days | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead time (time from start to deployment) | ___ days | ↓ 30% | JIRA/Linear/Git |

| Deployment frequency | ___ x / week | ↑ 2x | CI/CD metrics |

| WIP per person | ___ tasks | ≤ 2-3 | Kanban board |

| % time in meetings (makers) | ___% | ≤ 25% | Calendar analytics |

| Code review turnaround | ___ hours | ≤ 24h | GitHub/GitLab |

| Throughput (tasks finished/week) | ___ | ↑ 20% | Backlog analytics |

Rule: If 30-60 days after increasing the team none of the above metrics have improved, the problem wasn’t headcount. It was in the work system.

Summary

Hiring sounds like the simplest solution to a speed problem. In practice, without fixing the work system, it can make it worse. The key question isn’t “how many people do I need?”, but:

- Do I know where the bottleneck is?

- Do new people solve it or deepen it?

- Do I have a work system that absorbs new people without multiplying chaos?

If the answer is 3x YES—hire. If even one NO—first fix the system.

Because as Brooks said: “There is no silver bullet.” But there is good process engineering, clear ownership, and conscious work flow management.

That works. Always.

Bibliography