Root Cause Analysis (RCA): A complete guide for engineering, QA and business teams

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is one of the most effective tools you can introduce into a product or engineering team if you want to stop just putting out fires and start truly understanding where quality issues, delays and customer loss are coming from.

“The definition of a legacy system is that it’s a system without automated tests. And you could say that’s the cause of quality problems. In my opinion it’s a symptom – a symptom of problems with the quality of the process, not the code itself.”

RCA exists exactly for this: to go underneath the surface.

What is RCA (Root Cause Analysis)?

RCA (Root Cause Analysis) is an analytical exercise / method whose goal is to find the underlying cause of a problem – the “root” from which visible bugs and failures grow. It’s not about asking “who screwed up?” but:

- why did the system / process allow this bug to appear at all?

- what in the way we work, communicate, test or design failed?

“RCA, Root Cause Analysis, is an exercise – in short, it’s an analysis of the key reason, a tool for searching for the root of the problem.”

A well-run RCA:

- ends with concrete process changes,

- doesn’t stop at a one-off mistake (like “Chris forgot”),

- is repeatable and documented.

When should you use RCA in an IT project?

RCA is not something you do after every minor bug. It’s a heavyweight tool – you bring it in when:

- there is a serious production incident (system outage, loss of a client, quality disaster),

- an issue is repeatedly happening in the same area of the system,

- you need to change the process, not just ship a hotfix,

- you see that whole teams live in rework mode, not product development mode.

A very vivid example:

“Let’s imagine a situation. There’s a demo for a client. B2B, we’re going there to sell our application. Beautiful presentation and suddenly – Internal Server Error.”

That’s exactly the kind of moment when it makes sense to say: okay, time for RCA.

Other typical triggers:

- after a big deployment that “broke half the system”,

- when support or sales keep saying “they report the same thing over and over”,

- when a Product Owner hears from a client: “this is the third time already”.

| Repeated issues often point to deeper process or quality gaps. Pragmatic Coders’ Legacy Code Rescue services address this by combining root cause analysis, modernization, and automated testing to stop problems from coming back. |

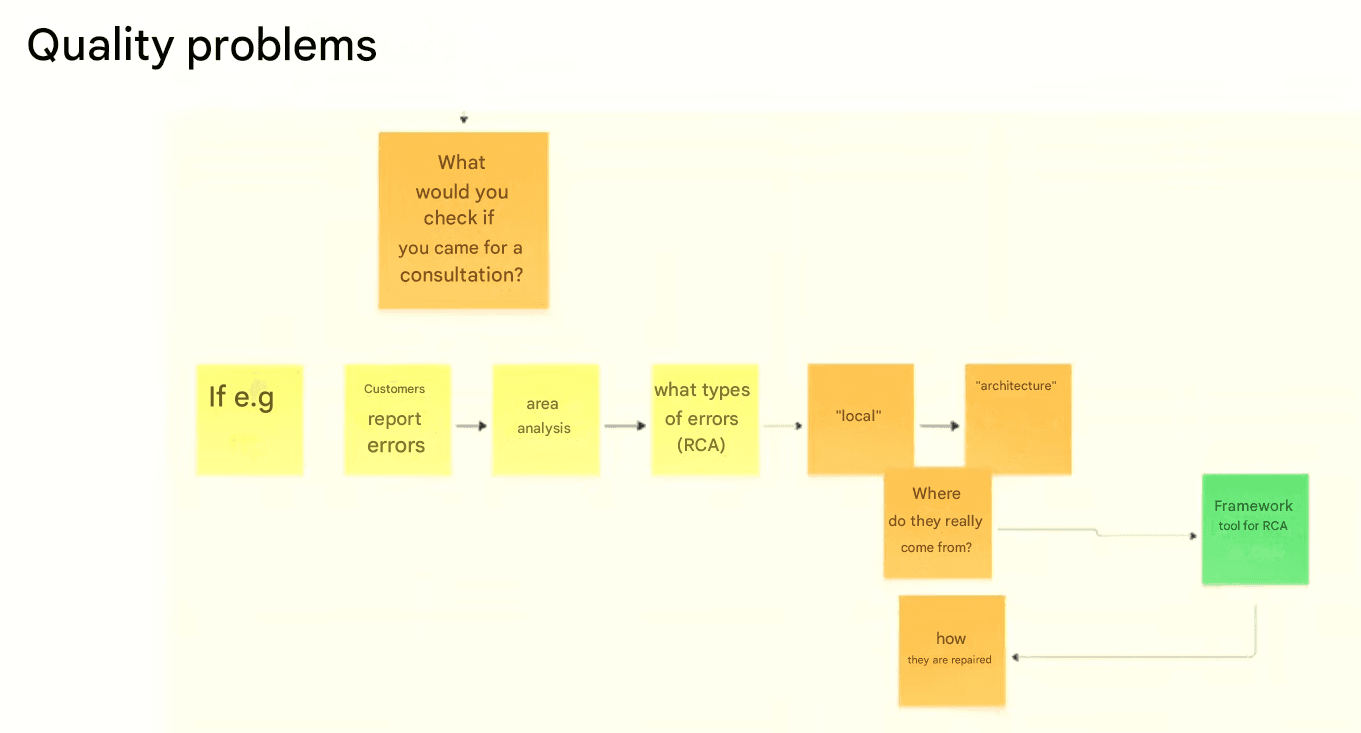

How does a good RCA look step by step?

The key thing: RCA is not a witch hunt. It’s a facilitated conversation where people have a safe space to say: “I forgot, I missed it, I didn’t know”.

“If we’re in an organization where the environment is safe, then we can openly say: Chris and Adam forgot, they overlooked it. And that’s okay.

It does not mean ‘let’s fire them’. Because that would mean we never get to the real root cause.”

RCA is not an audit – it’s an exercise in shared responsibility.

What are the stages of RCA?

- Gather the material:

- collected production bug reports (e.g. from Jira),

- logs, screenshots, customer tickets,

- who reacted, when and how.

“I would first deal with the bugs. Where do they come from? I’d collect reported bugs, analyze them, group them.

It may turn out that some parts of the system are more bug-prone or more important to users – that’s why they report these bugs.” - Appoint a facilitator:

- someone leads the conversation, asks questions,

- keeps asking “why?” in a lot of different ways,

- protects the meeting from turning into “who’s to blame”.

“What matters is the ability to facilitate and ask ‘why’ in a million different ways.”

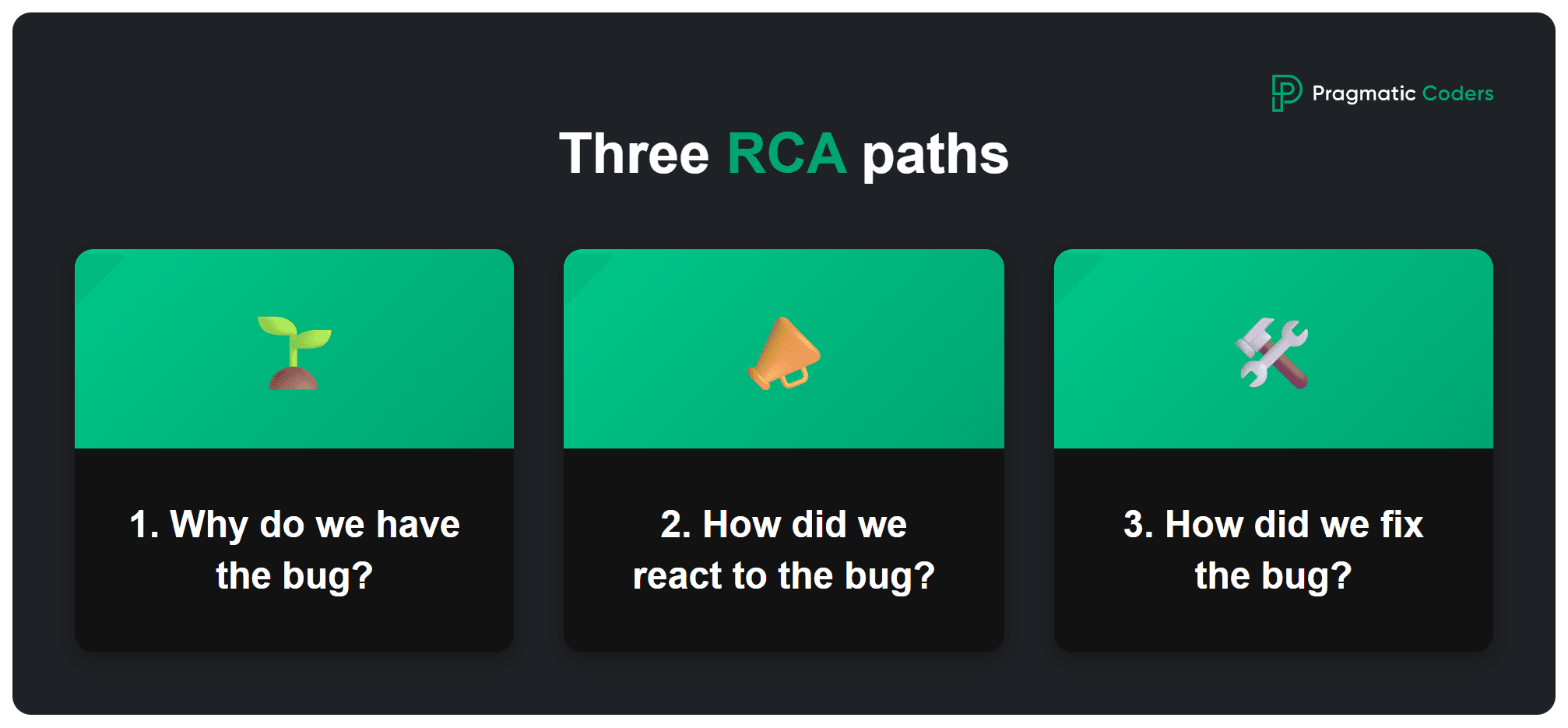

- Drill along three paths:

- Why do we have the bug?

- How did we react?

- How did we fix it, and is that enough?

- Formulate process-level conclusions:

- what do we change in DoR, DoD, standards, architecture, tests, refactoring.

- Implement and enforce:

- update the process (boards, workflow, Definition of Done/Ready),

- make sure it doesn’t remain just a nice Confluence document.

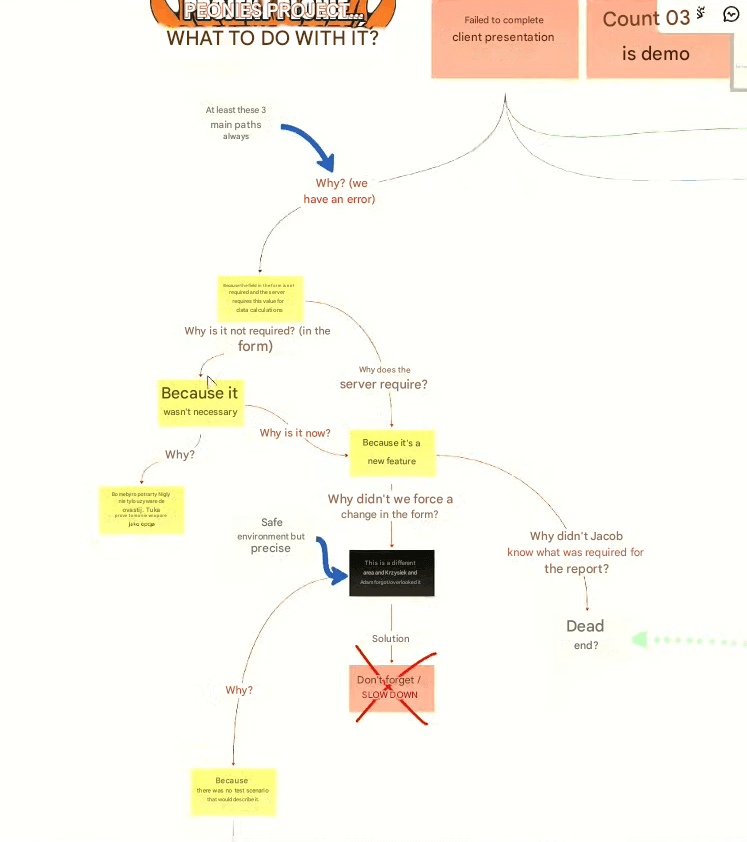

How do we drill into “why”? Three RCA paths

1. Why do we have the bug? – Refinement and Definition of Ready

Example: a form that allows you to skip a field required by the backend.

“Why do we have this bug? Because a field in the form isn’t required, and the backend requires this value for further calculations.

Why isn’t it required? Because it’s always been like that. It was never essential.

Why didn’t we force this change in the form? Because Chris and Adam forgot and overlooked it.”

This is where it’s easy to do the wrong thing:

“From there we can quickly go to: ‘let’s fire them’.

That would mean we never get to the real cause, so I don’t recommend it.”

RCA goes deeper:

“How were they supposed to know? There was no scenario describing it.

If we’d had good refinement, we wouldn’t forget about important scenarios.

But we limited refinement because we didn’t want long meetings.”

Process conclusion:

- better refinement,

- explicit questions about scenarios and error paths built into Definition of Ready (DoR),

- a habit of thinking in test scenarios: “what could go wrong?”.

“The solution is almost always process-related, because it’s almost always the process’s fault.”

Example of the first path of RCA – done in Miro

2. How did we react to the bug? – Definition of Done and CTA

A short story:

“Our sales guy, Jakub, wrote in the channel:

‘I can’t get through the form, I can’t finish the demo, I need help.’

It turned out he had hit a bug he could have got out of – you just needed to fill the start date field.

But he didn’t, because the error message Internal Server Error didn’t say what was wrong.”

This is the second RCA path: the reaction of the system and people.

- Did the error message help the user recover?

- Was there an instruction (CTA) telling them what to do next?

- Did support know what to reply?

“It would be enough to add to Definition of Done that every error has to have a call to action.

So it tells the user what to do next.”

And a key nuance:

“You might say: the product owner or analyst didn’t specify what exactly should be in that message.

But if we have this in Definition of Done and the PO/analyst is sick, gone, whatever –

the developer can still come up with some not-perfect text, but it will at least be a CTA.

And in consequence we wouldn’t lose the client.”

Process conclusion:

- We add to Definition of Done:

👉 “Every error message must have a clear description + call to action.”

| Helpful error messages and calls-to-action need empathy and UX insight. That’s why our Product Design process includes RCA learnings in the Definition of Done, making sure every message or system state is clear and useful. |

3. How did we fix the bug? – Historical data and durability

Third path: is the fix complete?

“We added the field as required and we’re done, right?

But is that enough? No.

Why?

Because there are 1,217,307 users who already went through that form, and when they try to generate a report, they will still get an error.”

Classic case:

- the hotfix works for new data,

- but historical data remains inconsistent.

“We’d get to the point that we should add to DoR a question:

‘After this change, do we need to take care of historical data?’”

Process conclusion:

- We add to Definition of Ready a technical question:

👉 “Will this change require any action on historical data (migration, recalculation, enriching)?”

Typical process outcomes from RCA – example table

| Problem found in RCA | Root cause | Process change (DoR / DoD / practices) |

|---|---|---|

| Field in form not required, backend requires it | No scenario discussed in refinement; cutting discussion “to save time” | DoR: questions about scenarios and validations; work with examples and edge cases |

| Internal Server Error with no explanation | Default generic message, no standard for errors | DoD: “Every error message must have a CTA”; minimal content standard |

| Report generation fails for old records | Hotfix only fixed new records; no consideration for historical data | DoR: “Does this change require actions on historical data?”; technical task for data migration |

| Typo in product type (“soup” vs “soop”) | Manual string entry, no validation / enums | Introduce enums, validators, linters; code reviews focusing on hard-coded strings |

| No test that would catch the bug | No habit of designing tests at DoR; no automation | Introduce automated testing strategy; DoD: “tests defined and/or implemented”; regression tests for critical flows |

How does RCA help you talk to the business in money?

“In my case we lost a client whose lifetime value is almost one and a half million dollars.

Because of a small bug in the demo.

A missing basic, standard thing — a nice call to action in an error.Business likes money, and business likes to see the impact of our actions on their financial result.”

This gives you a storyline:

- technical bug → user experience → lost client → specific cost (LTV etc.).

Another example:

“It might be that the online shop is down.

Service unavailability is a concrete cost.

You can show the business: on Black Friday you lost this much money because your shop wasn’t ready for that traffic.”

And on rework:

“Let’s say we have three, four, five dev teams, and one or two are constantly patching bugs.

Look at what that costs. You can calculate it in dollars.

See how much production capacity we waste on fixing bugs.

This stat helps you talk to the business and say: ‘That’s not okay. We need to pay off the debt. It will cost, but it will pay off because we can translate it to dollars.’”

How to turn this into numbers:

- hours per sprint spent on rework vs new features,

- value of lost opportunities (downtime, failed demo),

- LTV of lost / frustrated customers.

Thanks to RCA you can go to the business not with “we want tests because we like quality”, but:

“Here are the concrete incidents, their process-level causes, their cost in dollars – and here are specific changes that will reduce these costs in the future.”

What is the role of automated tests in RCA and rework?

“The definition of a legacy system is that it’s a system without automated tests.

You could say that’s the cause of quality problems.

In my view it’s a symptom of poor process quality, not poor code.”

RCA very often ends with:

“Tests would have prevented this.”

Tests as a checksum

“Tests are a checksum.

The system has grown over the years, we don’t remember every rule any more,

but automated tests, regression tests, protect us.If a month from now we change the coupon logic, a test will turn red if the old logic (say, 10% discount) gets broken.

Someone has to intentionally change the test to 15%.”

Tests and rework

“Why does the business need tests?

To reduce rework – the number of bugs and tasks that come back to developers.

We finish a sprint, deploy, then there’s feedback because of bugs and we have to fix things.”

So, if after multiple RCAs you keep seeing:

- “a test here would have caught it”,

- “here too a test would’ve helped”,

you now have a strong argument:

- tests aren’t an “engineering luxury”,

- they’re an investment in reducing rework and safer deployments.

RCA and technical debt: Tidy First and incremental refactoring

RCA often uncovers that the real problem is not “this bug right now”, but:

- massive coupling between modules,

- code readability at an “archaeology” level,

- no separation of concerns and no testability.

So you might ask:

“How do we start reducing technical debt without stopping work on new features?

If we’re not able to, or it doesn’t make sense to rewrite the system from scratch, and at the same time we don’t want to leave it as is, we’re left with one option: evolution of the current solution — that is, incremental refactoring.”

On coupling:

“Most problems in software development are related to coupling.

One module is tied to another even though it shouldn’t be.

If the discount code doesn’t work, you can’t pay for the cart.To get rid of coupling, you need to refactor module by module, extract them.

It’s hard, but by evolving the current solution, we introduce smaller changes and get feedback very fast.”

On Tidy First:

“I recommend the book Tidy First.

The idea: the developer slightly improves the code while making changes – not after themselves, but before themselves.

Small steps that mean today the system is a bit better than yesterday.”

RCA is your radar that shows:

- where technical debt already hurts,

- which areas need to be touched first,

- which practices (refactoring, enums, modularity) you need to formalize.

| This mirrors our Legacy Code Rescue service — where we help clients move from firefighting to proactive evolution. RCA sessions often identify code debt hotspots, and our teams turn them into structured refactoring roadmaps that reduce risk without halting feature delivery. |

How to measure the effects of RCA? – useful metrics

“Always measure and make sure those metrics are visible.

Whether it’s lead time, DevOps metrics, number of bugs (and it may go up when we start fixing things and exposing new parts of the system), or test coverage.Some metrics are outputs, process metrics, but we should also measure outcome – how users react to what we do.”

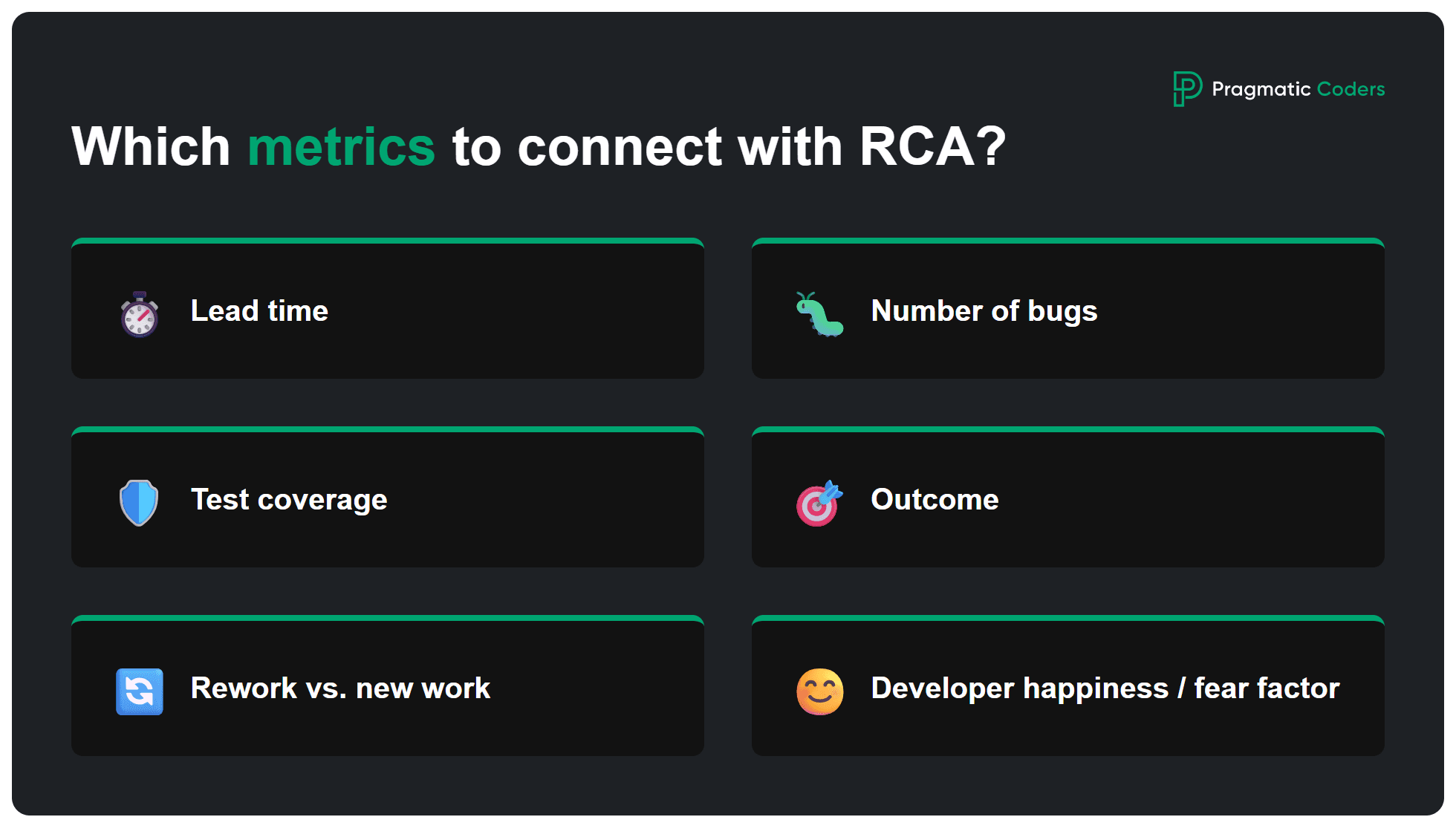

Which metrics to connect with RCA?

- Lead time (idea/bug → production),

- Number of bugs (especially in the same area),

- Test coverage,

- Outcome (user reactions, NPS, retention),

- Team capacity used for rework vs new work,

- Developer happiness / fear factor.

“We can start with a simple survey:

‘Are you afraid of deploying changes on Friday?’

It helps us see whether thanks to process changes things are ‘better than yesterday’.”

And a very human closing thought:

“Legacy projects are big, system inertia is huge.

I’m frustrated because I’d like to be five steps ahead, and we’re still dealing with fires.Then it helps to have metrics and see: hey, it’s better than it was yesterday.

Maybe slow, maybe not perfect, but better than yesterday.”

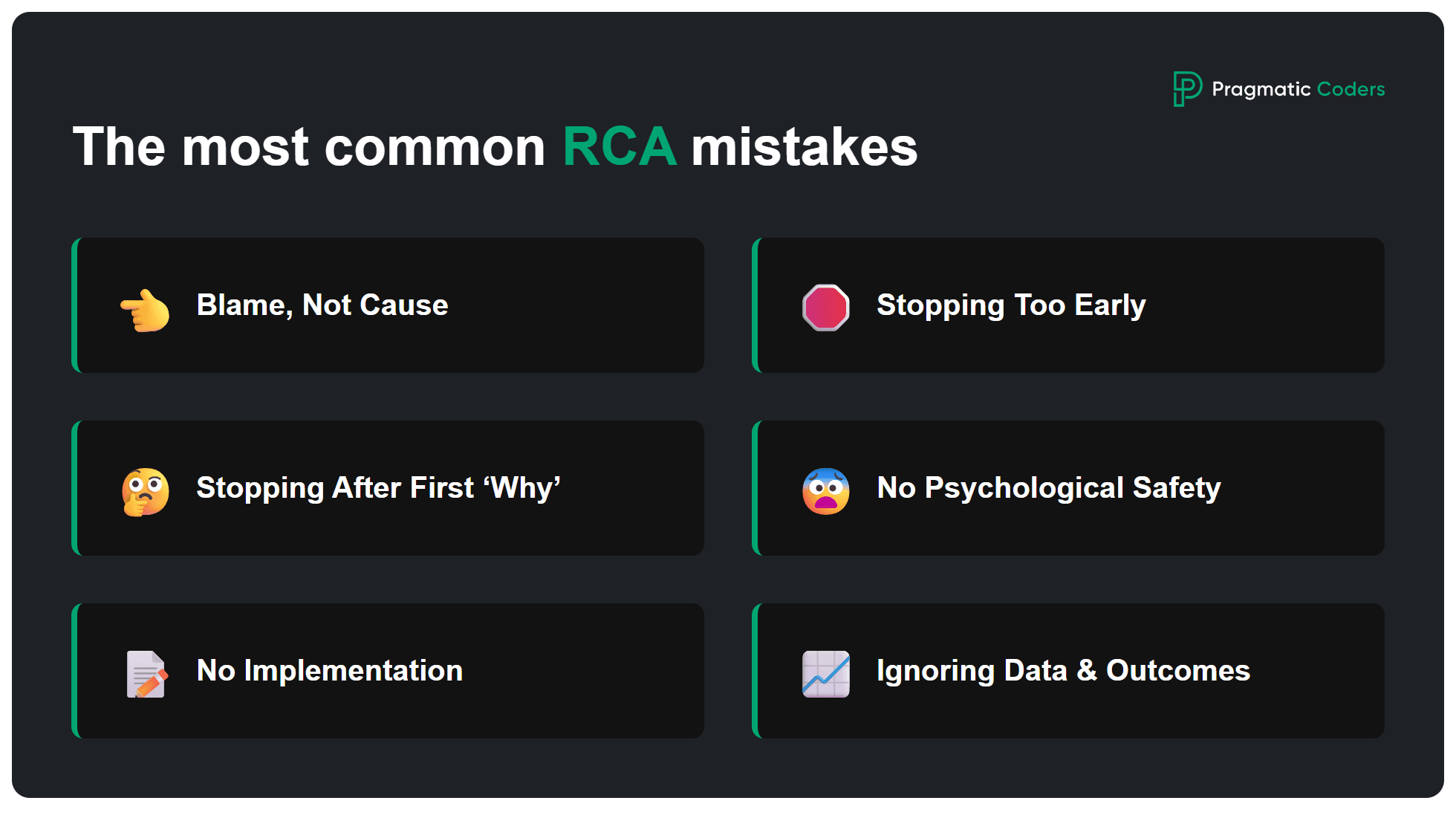

The most common RCA mistakes

- Looking for a person to blame, not a root cause.

Stopping at “Chris and Adam forgot” without asking “why was it possible to forget?”. - Stopping after the first ‘why’.

The real cause is usually 3–5 levels deeper (refinement, lack of standards, missing validation, debt). - No psychological safety.

If people are afraid to admit they missed something, RCA turns into theater. - No implementation of conclusions.

You have a nice doc in Confluence, but DoR/DoD, checklists, boards stay the same. - Ignoring historical data.

Focusing only on “we fixed the bug” without considering existing records / users. - Not measuring outcomes.

Without metrics it’s hard to say if your RCAs actually improve anything.

Sample RCA meeting template (ready to reuse)

You can use this as the skeleton of your RCA meeting:

- Meeting goal (5 min):

- Which incident are we analyzing?

- What do we want to understand / decide / change?

- Reconstruct the story (10–15 min):

- What exactly happened, step by step?

- What did the user / client see?

- What do the logs say?

- Three paths (20–40 min):

- Why do we have the bug? (refinement, requirements, decisions)

- How did we react? (messages, support, internal communication)

- How did we fix it? (is it complete, does it handle historical data?)

- Process conclusions (15–20 min):

- What do we add/change in DoR?

- What do we add/change in DoD?

- Which standards / best practices do we introduce?

- Implementation plan (10 min):

- Who owns what action?

- How will we know the change works (metrics)?

- When do we come back for follow-up?

FAQ – common questions about RCA

Is RCA the same as a post-mortem?

No. Post-mortem is a broader reflection on an incident or project (what went well, what didn’t, lessons learned).

RCA focuses specifically on root causes and process changes to prevent recurrence.

Do we need RCA after every bug?

No. RCA makes sense mainly after:

- critical incidents,

- repeated bugs,

- events with big business impact (lost client, Black Friday outage, long downtime).

For small bugs, a mini-retro is often enough.

How long should one RCA session take?

Typically: 30–90 minutes.

The key is:

- good preparation of inputs,

- a focused conversation,

- reaching 2–5 actionable process changes.

Who should participate in RCA?

- Developers / engineers familiar with the area,

- Product Owner / analyst (business view),

- sometimes support / sales (user voice),

- a facilitator (keeping structure and safety).

Can RCA be done remotely?

Yes. Tools that work well:

- Miro / Mural (visual maps),

- Google Docs / Confluence (live notes),

- Zoom / Teams / etc. with cameras on (helps with trust).

How to start introducing RCA in the organization?

- Start with one concrete incident,

- run RCA “by the book”,

- derive 2–3 real process improvements,

- show it to the business in numbers (costs, rework) and as specific improvements.

Summary: RCA as a habit – “better today than yesterday”

RCA is not a one-off “crisis tool”. It’s part of a culture:

- asking “why?” instead of “who’s at fault?”,

- thinking in systems and processes instead of individuals,

- connecting technical incidents with real business costs,

- measuring progress and being happy that today is a little better than yesterday.

And it’s worth remembering these words:

“What helps me is saying to myself: make the world a little better every day – my world, my product.

Sometimes I’m frustrated because I want to be five steps ahead and we’re still dealing with a fire.

Then it’s great to have metrics and see: hey, it’s better than it was yesterday.

Maybe slow, maybe not perfect, but better than yesterday.”

For us at Pragmatic Coders, RCA is not just a method — it’s part of how we work. Whether we’re building scalable banking apps for Atom Bank, or modernizing AI-powered healthcare platforms like WithHealth, we always analyze the why behind issues, not just the what. That’s how we keep improving products and processes, one RCA at a time. If that’s what you’re looking for in a software partner, don’t hesitate to contact us.