Vendor Lock-In in Custom Software: How to Spot & Prevent It

The global IT outsourcing market reached USD 618.13 billion in 2025 and is projected to hit USD 752.08 billion by 2031. Behind that growth lies a hidden risk: many companies paying for custom software don’t actually control what they’ve paid for. They assume ownership because they funded the project. In reality, they lack access, documentation, or the practical ability to switch vendors.

This article explains how vendor lock-in develops in IT projects, why it threatens your control over the product, and how to prevent it. I cover six warning signs, a quick self-assessment, and practical safeguards.

Key Points

|

Why Custom Software Creates Hidden Dependencies

Vendor lock-in occurs when switching providers becomes so costly or risky that you feel stuck. In custom software development, this dependency grows from the relationship between you and the company building your product.

Lock-in develops during long-term engagements. Research describes this through the concept of “asset specificity”—custom code creates investments tied specifically to one vendor relationship. These relationship-specific investments increase switching costs over time. The more tailored the solution, the harder it becomes to extract yourself.

This often happens unintentionally, during normal project work. Your vendor isn’t necessarily trying to trap you. But without deliberate safeguards, dependency builds quietly in the background.

Why does this matter strategically? Lock-in affects product ownership and roadmap control. It limits your ability to change direction, adopt new technologies, or switch partners when circumstances demand it. Invisible costs compound over time. By the time you notice, switching may cost more than staying.

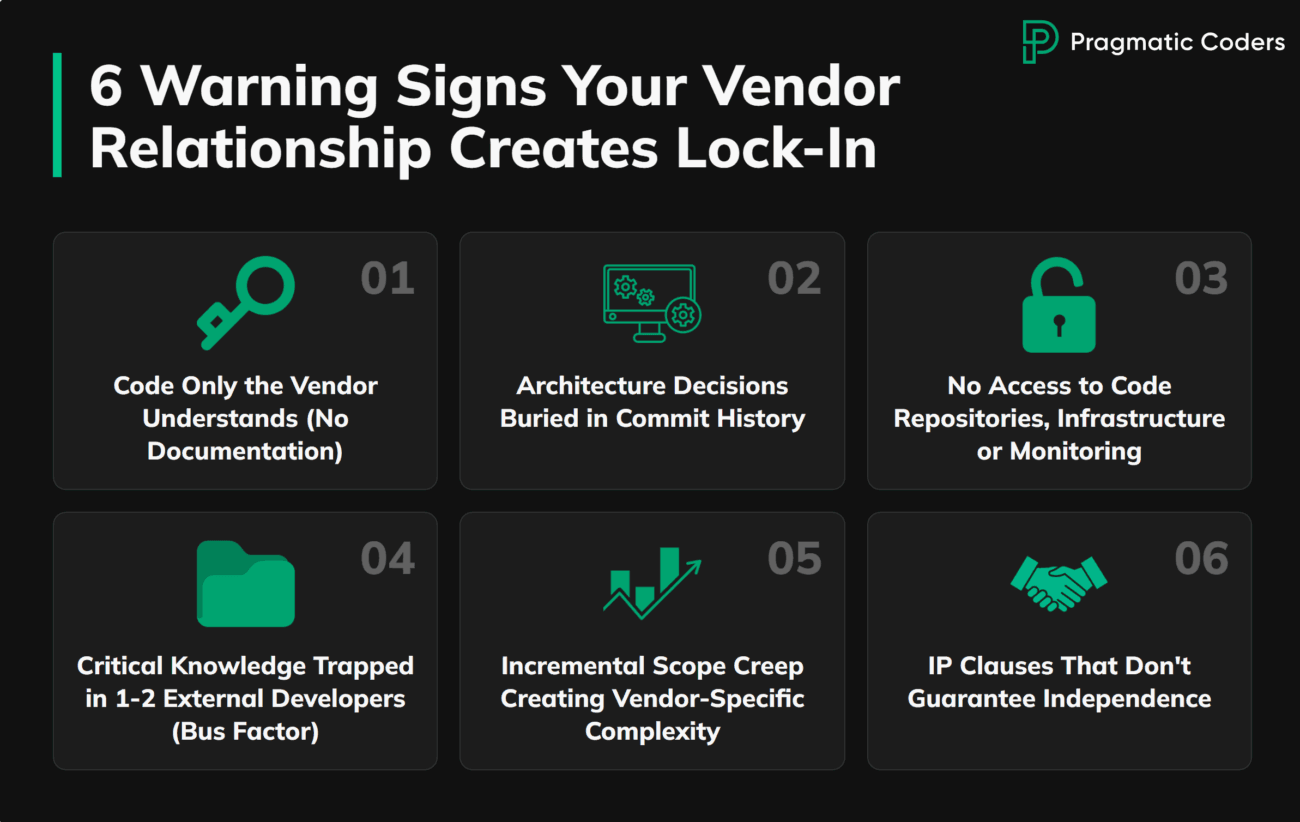

Six Warning Signs Your Vendor Relationship Creates Lock-In

Lock-in develops through non-obvious mechanisms during software delivery. Recognizing them early is the first step to prevention.

Here are six patterns to watch for:

Code Only the Vendor Understands

Custom-built code written without external readability in mind creates hidden dependency. If there’s no onboarding documentation or code walkthroughs for your team, knowledge stays locked inside the vendor’s organization. You can’t evaluate the code quality or make changes without their help.

Undocumented Architecture Decisions

Key architectural choices get buried in commit history instead of being explained or recorded. You have no visibility into why the system is built the way it is. Only the original developers can answer your questions about design trade-offs.

No Access to Repositories and Infrastructure

When the vendor doesn’t grant you access to repositories, environments, CI/CD pipelines, or monitoring systems, you can’t see what’s happening with your product. You can’t verify their work or diagnose problems independently. And when you decide to end the engagement, the vendor can even block the project handover because they control access to the code and infrastructure.

Knowledge Trapped in a Few Heads

When critical operational knowledge exists only in the heads of a few external developers, you’re entirely dependent on them. In the industry, this is called “bus factor”: how many people would need to get hit by a bus for the project to fail. When that number is 1-2, you’re in a high-risk zone. If those people leave the project, you lose access to informal knowledge about how your system actually works.

Research shows that rebuilding that knowledge and competence are major challenges when regaining control over the project. Reconstructing this knowledge in a new team takes months and is costly.

Incremental Scope Creep

Each new feature adds complexity only the vendor can maintain. Scope extensions deepen dependency over time. Eventually, the vendor becomes your only realistic option. Switching would mean reconstructing the reasoning behind years of decisions.

IP Clauses That Don’t Guarantee Independence

Your contract says “client owns the code.” But it doesn’t say another team can modify it. The vendor keeps rights to components they reuse across projects: their framework, auth modules, admin tools. When you try to hand over the project, you discover chunks of the system are shared IP. The new team must rewrite those parts or negotiate with the old vendor. On paper, you own it. In practice, switching vendors means rebuilding.

What Vendor Lock-In Really Costs You

Vendor lock-in costs you in three ways: financially, operationally, and strategically. These costs often exceed what you’d pay to switch providers.

Financially: you lose negotiating power when the vendor becomes irreplaceable. Price increases get disguised as “complexity surcharges” or “legacy maintenance.” Cost escalation gets framed as constraints you have no way to verify. You’re told something will take three months, and you can’t challenge the estimate because you don’t understand the codebase.

Operationally: lock-in reduces your ability to onboard a second vendor or build an internal team. Research confirms that “organizational build-up” is the hardest part of regaining control. You also face operational fragility when key vendor staff leave or vendor priorities shift. Your product depends on individuals, not documented systems.

Strategically: once initial development wraps up and you want to expand, you may find only your current vendor can do it. They’re the only ones who know the system well enough to make changes safely. New features may require waiting for their team. Tech changes may need their buy-in. Your product’s future then depends on the vendor, not you.

How Dependent Are You on Your Vendor? Let’s Find Out

Answer “yes” or “no” to each of the following questions.

- Can you access all source code without asking the vendor?

- Do you have credentials and access to production environments if needed?

- Is the system documented well enough for a new team to work on it?

- Are the rationales behind key architectural decisions documented somewhere?

- Does your contract allow you to assign development or modification of the code to another team?

Count your “yes” answers. Zero to two: you are heavily dependent on your current vendor, and switching would be difficult and costly. Three to four: you are independent in some areas, but switching vendors still requires preparation. Five: you are in a good position and have a real ability to switch vendors quickly if needed.

If your score concerns you, do not ignore it. Start by validating what is really happening inside the project. These 15 questions to audit your IT project status will help you verify access, transparency, technical health, and real delivery before you make any vendor decision. If the answers raise more red flags, an independent audit will give you a clearer picture and concrete options. Need help? Contact us.

Why IP Rights Don’t Protect Against Vendor Lock-In

Many companies formally “own the IP” but lack real, operational control over their product. The gap between formal ownership and practical control is where lock-in lives.

Formal ownership means you have legal title to the code. Practical control means you can use, modify, and transfer the software without vendor cooperation. Research shows that IP sharing arrangements often leave clients with limited practical rights. On paper, the code is yours. In practice, to develop it without your current vendor, a new team must first reverse-engineer the code and reconstruct the logic behind every decision.

Why don’t IP clauses alone guarantee independence? Several reasons:

- You may be missing access to repositories and environments.

- Documentation may be insufficient for a third-party takeover.

- Ownership terms may be vague enough to quietly increase dependency.

- Shared IP arrangements may limit your rights to modify or transfer.

What to Include in Your Contract and How to Oversee Your Project to Avoid Vendor Lock-In?

Only a combination of proper contract clauses and good project management practices effectively prevents vendor lock-in.

Contract Clauses Worth Including

- Clear assignment of copyright to custom code

- Guaranteed access to source code, repositories, and documentation

- Commitment to documentation and ongoing knowledge transfer

- Exit terms: transition period, obligation to support project handover

Research shows that declaring ownership transfer alone isn’t enough. You need specific clauses.

Good Practices During Vendor Collaboration

- Require complete documentation – enough for a new team to onboard

- Make sure coding standards and Definition of Done are established at the start

- Ensure you have easy access to repositories and environments

- Participate in regular progress reviews (e.g. Sprint Review)

It’s easier to establish these from the start than to catch up later.

When to Request an Independent Audit?

It’s worth commissioning it when:

- You’re about to renew a long-term vendor contract

- Costs or timelines seem unreasonably high and you have no way to verify them

- Key vendor staff have left and there’s no documented knowledge about the project

- You’re considering bringing development in-house or switching providers

- Leadership asks “what would it take to change direction?” and no one knows the answer

An independent project audit is more than just a code review. We start by understanding the product, its goals, and its users. We talk to you, your team, and users to uncover problems that aren’t visible in the code. Only then do we review architecture, documentation, access, and contract terms. Based on this, we prepare an action plan or recommendations.

At Pragmatic Coders, we offer project rescue services that include such audits.

Conclusion

Vendor lock-in builds gradually, often unnoticed. Small decisions, documentation gaps, and lack of project control compound until switching vendors becomes difficult.

This dependency can be measured and reduced. If you have doubts, start with an audit. A clear picture of your situation is the foundation for action.