Where startup money comes from: The REAL explanation

In today’s article I’ll talk about where money in startups comes from. If you’re a founder (or thinking about launching your own startup) this one’s definitely for you. You’ll learn, among other things:

- Where startups get their money (sure, it can be from paying customers, but that’s extremely rare early on);

- Types of investors, where those investors get the money they invest in startups, and what really drives their decisions.

The knowledge you’ll get from this article will be valuable and helpful when you start looking for funding. Once you know where a fund’s money comes from and how those funds actually work, it gets much easier to talk to them and to choose which funds or investors are worth approaching at a given moment and stage in your startup’s life cycle.

Where does money in startups actually come from?

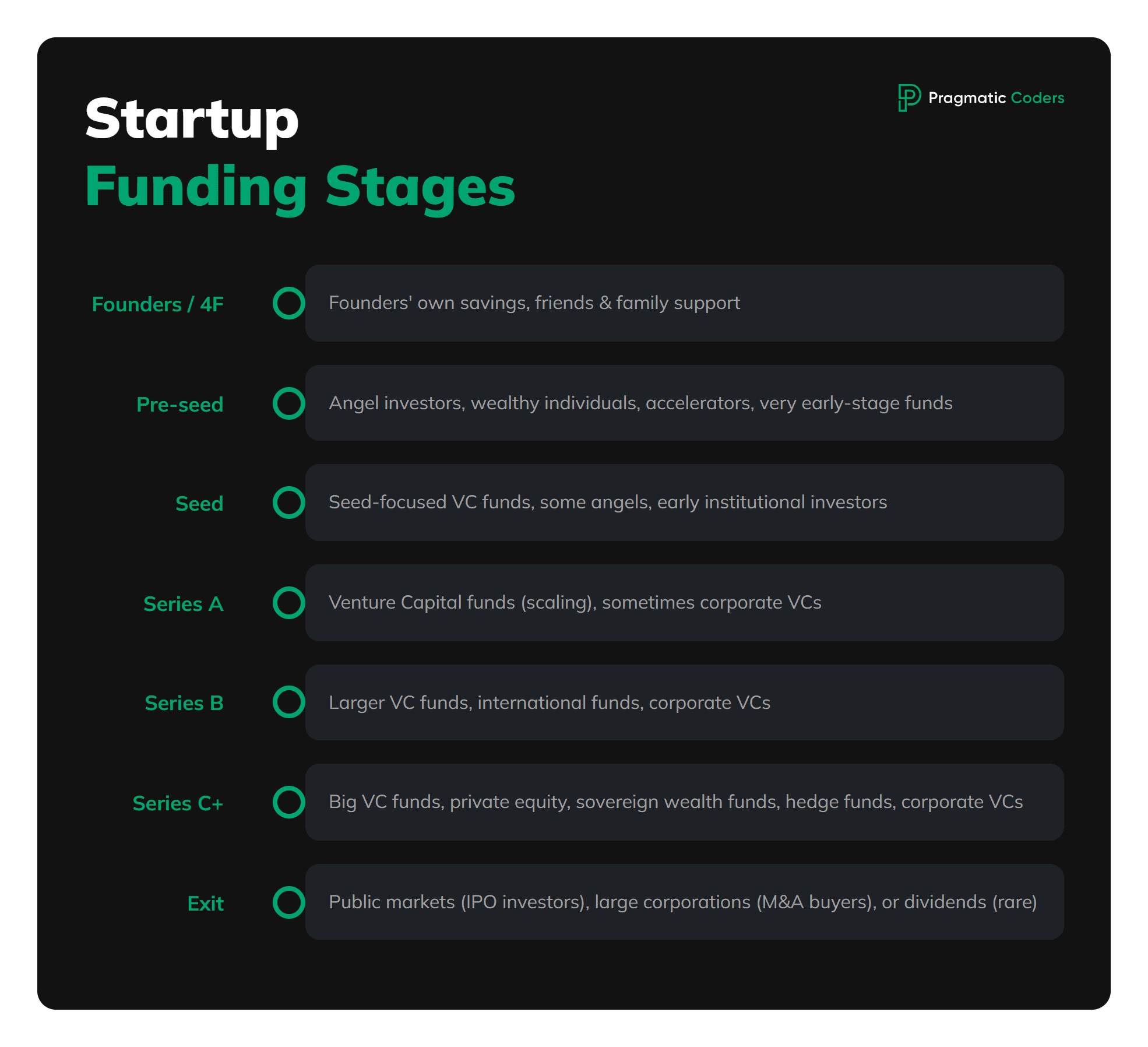

Startup money usually comes from investors, not customers. Founders often start with their own savings or support from friends and family, then raise money in rounds.

To answer how to raise financing for a startup, we first need to look at where the money in startups comes from in the first place and what the investment process looks like. It’s worth starting with what “funding rounds” are, what order they usually follow, how many there can be, and how it works for most-though not all-startups.

Typically it looks like this: the very first money in a startup is the founders’ own money, or simply their time and energy put into building the product. Sometimes founders also raise a bit of capital; of course in exchange for the promise of future equity (from friends or family). That’s the so-called 3F (or sometimes 4F) round. 3F means Friends, Family and Fools; 4F adds Founders. “Fools” because, as we all know, very early-stage startup investing is extremely risky and often doesn’t work out-so you can look a bit foolish if you back the wrong one.

What’s the difference between pre-seed and seed rounds?

Pre-seed is usually small checks from angels or wealthy individuals before the product is built. Seed comes next, often with VC funds doing deeper due diligence.

What happens in Series A, B, C and all the later rounds?

Later funding rounds are labeled alphabetically (Series A, B, C, etc.) and typically involve bigger checks at higher valuations. The further you go, the more traction and proof you’ll need to raise.

There can be several later rounds (sometimes, in extreme cases, a dozen or more) labeled alphabetically: Series A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and so on. The most round-heavy startup I’ve personally encountered had raised up to an H round, though there are companies that go even further.

The general rule: the later the round, the larger the check and the higher the valuation. There are exceptions (so-called down rounds) when a startup hasn’t delivered on promises or hits financial trouble and raises to survive or rebuild. In those cases the valuation drops. But in most cases each round happens at a higher valuation, so investors get smaller equity percentages for the money they put in. That’s by design: early investors took more risk amid more uncertainty, so they invested at lower valuations and received larger stakes for less money.

How do startup investors make their money back?

Investors get returns through exits: IPOs, acquisitions, or, rarely, dividends. Most aim for a big win when the company is sold or goes public.

After many funding rounds – a process that can take several, even a dozen or so years – startups eventually aim to return capital to investors. There are a few routes:

- IPO (going public),

- Acquisition by a bigger player (e.g., Microsoft, another corporation, or sometimes a direct competitor),

- Or, much more rarely, dividends – when a startup generates substantial profits and shares them with shareholders.

How are rounds actually done? Each time, the company issues new shares. Existing shareholders can participate, but if they don’t, their percentage ownership gets diluted. Imagine equity as a cake: each investor gets a slice proportional to their investment. If the whole cake grows and you don’t increase your slice, your percentage of the cake shrinks.

How does issuing new shares affect ownership-and why does your cap table matter from day one?

Each funding round gives less equity to old shareholders. If you manage your cap table early, founders stay motivated longer.

That’s why cap table management matters from day one: structure ownership so the equity lasts and so that, by round three or four (or earlier), founders aren’t already reduced to a demotivating minority.

Later minority can be fine; what you want to avoid is getting there too early or ending up with a stake so small it no longer motivates you to push the company forward. Keep a structure that preserves founder motivation to keep building.

Who are the people and funds investing in startups? Types of investors

Before you start fundraising, or if you want to get better at it, you should understand who the investors are and how they invest. The types mirror what you see globally, though the proportions differ (more on that in a second).

Let’s focus on the main types, what characterizes them, at what stage they invest, and roughly how much capital they put in.

Angel investors and syndicates

Angels are people who invest their own money early and often share their experience and contacts. Syndicates are groups of angels pooling capital and due diligence.

We already mentioned 3F (friends, family, and fools) – individuals who back founders at a very early stage with small amounts to help them take their first steps. These people are often motivated by relationships and emotion: they like the product, trust the founders, and decide quickly.

Next are angel investors: individuals with capital. Sometimes they manage a broader portfolio; sometimes they focus solely on startups.

In Poland angels typically invest from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands US dollars (~50,000 PLN to ~500,000 PLN). Beyond money, angels often bring expertise and networks; many are experienced operators or repeat startup folks. They can also help with later rounds, opening doors to VC funds and even helping you communicate with them.

A related form is the angel syndicate – it’s not a different investor type, but a group of angels investing together. They can do better due diligence collectively, share deal flow, and write larger combined checks, while sharing risk among members and comparing notes on why to invest (or not).

VC fund

The next, more professional category is Venture Capital (VC) funds. Funds vary, but most look similar inside. A key point: VCs usually invest other people’s money. Whose? We’ll get to that next.

Who are LPs and GPs, and what do they actually do in a VC fund?

LPs provide the capital behind the fund, while GPs run it day-to-day and choose which startups to back. LPs get returns if the fund succeeds; GPs earn carry on profits.

Inside a fund there are two key groups: General Partners (GPs) and Limited Partners (LPs). LPs are the investors in the fund. They typically pay a small amount up front (the management fee) and commit a larger amount to be drawn down later, when the fund finds startups worth investing in. This way LPs don’t have cash sitting idle for months or years; they keep their liquidity until the fund calls capital for specific deals.

How do VC funds operate behind the scenes?

VCs raise money from LPs, invest over a few years, and support startups to maximize outcomes. Most funds run on a 10–15 year cycle.

GPs first raise commitments from LPs for a fund expected to run about 10–15 years. They then aim to invest most of the capital within 3–5 years-so there’s time for those investments to mature and (hopefully) return capital within the fund’s lifespan. GPs source deals, evaluate them, decide where to invest, and then support founders post-investment to maximize the chance of strong outcomes.

Corporate Venture Capital-and how does it differ from regular VC?

Another type is Corporate Venture Capital. Structurally similar to VC, but typically with one LP – the corporation itself (e.g., Microsoft, a bank, etc.). Sometimes the LP is a government-related organization distributing grants or EU funds. Their goals can include strategic benefits, not just financial returns.

Family offices, grantmakers, and government funding

Family offices invest private wealth, usually quietly and across many sectors. Governments and grantmakers support startups through formal, rules-heavy programs, especially in markets like Poland.

You’ll also find family offices – wealth managed for a wealthy family (or a few related families), sometimes by a dedicated professional. These can have sizable budgets and invest across asset classes, including startups.

Then there are government agencies and other grantmakers. They may invest indirectly (as LPs in VC/fund-of-funds structures) or directly via grants to startups. Many in Poland will remember EU programs like the old “8.1” action that provided innovation grants. These processes are formal and rule-heavy, both for funds seeking public capital and for startups applying directly.

Crowdfunding

Equity crowdfunding lets the public invest small amounts into startups. It’s possible, but takes a lot of marketing and isn’t always cost-effective.

Finally, there’s equity crowdfunding: platforms where you list your startup and people from around the world-after basic verification-can invest, often very small amounts across many startups. It’s an option, but it’s hard: you must reach enough people and convince them, and platform fees/marketing can be significant, sometimes regardless of whether you hit your target.

How is startup funding in the U.S. different from Poland?

In Poland, over half of startup capital comes from public money, while in the U.S. it’s mostly private, like pension funds and endowments. This shapes how funds behave, who they can back, and when.

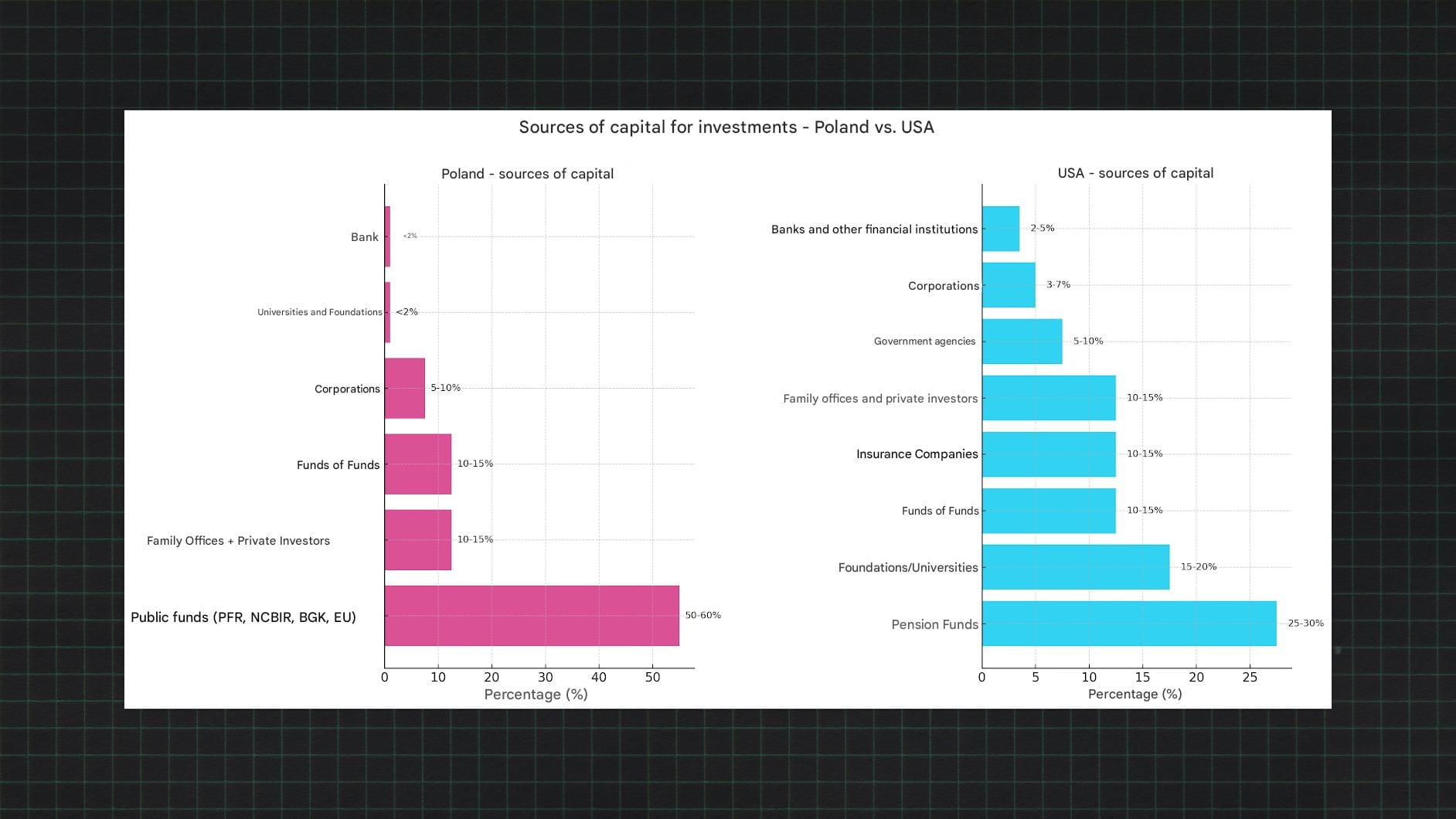

I prepared a comparison showing who supplies the capital that ends up in VC funds investing in startups in Poland vs. the United States. This strongly influences how Polish vs. U.S. VCs decide which startups, at what stage, and how to fund them.

In Poland, about 50–60% of the capital comes from public sources, e.g., PFR, NCBR, BGK, or EU institutions. Another 10–15% comes from family offices and private investors (angels), who collectively put meaningful money into many small rounds across many ideas. 10–15% comes from fund-of-funds. 5–10% from corporates investing into VC. Around 2% from universities/foundations, and roughly 1% from banks.

In the U.S., the mix looks very different.

- 25–30% comes from pension funds. That means if your startup raises from a U.S. VC, up to ~30% of the money might ultimately be Americans’ retirement savings being invested for growth.

- 15–20% comes from foundations and universities (many U.S. universities have large endowments).

- 10–15% comes from fund-of-funds. 10–15% from insurance companies.

- ~10% from private investors/family offices.

- 5–10% from government. 3–7% from corporates.

- And 2–5% from banks and other financial institutions.

As you can see, Poland has over half of startup-bound capital coming from public programs, whereas in the U.S. government money is only ~5–10%. This affects the market: in Poland, processes tied to public funds are often more formalized and rule-constrained-for example, some funds can’t invest alone, need co-investors, have rules about follow-on rounds, etc.-which limits a fund’s autonomy.

How does the economy shape when and how money flows into startups?

Interest rates, public funding cycles, and market confidence all influence how active investors are.

Why is this useful when you’re fundraising? Because knowing where the money flows from helps you decide whom to talk to and when.

For example, if there are no EU/government programs active in Poland for a while, VC funds that rely on public money may simply not have capital to deploy.

- When new grants or EU programs appear, expect VCs to be more active – new funds launch and start looking for startups. That’s a good moment to engage.

- When public-money-heavy funds are quiet, it can be smarter – especially early on – to focus on angels rather than spending time with VCs that currently don’t have dry powder. Only a handful of Polish funds are mostly or fully privately financed and stay active through such cycles.

Globally, watch interest rates.

- When rates rise, U.S. pension funds, for example, may shift capital into safer, inflation-protected instruments instead of riskier VC – so overseas VCs can become less active. Higher rates can also make individual angels more risk-averse.

Also watch broader macro volatility.

If geopolitical decisions or market shocks increase uncertainty, even “safe” assets can look shakier. In such times, some investors may view startup risk differently – not necessarily lower in absolute terms, but lower relative to the turbulence elsewhere – so VC appetite can return. Keep in mind: these markets have inertia measured in months or even years. An event six months ago might only show up now in how active VCs and angels are.

Final thoughts

That’s everything on where money in startups and investment funds actually comes from. Understanding where the money comes from and how funds work helps you pick the right investors – and talk to them at the right time.

Have funds already and looking for a product team to build it? Leave us a message – we got decent startup experience, and, most importantly, we work to give you the most value using the least amount of money. Contact us >>>

FAQ

What are PFR, NCBR, and BGK?

PFR – Polish Development Fund (Polski Fundusz Rozwoju)

A state-owned financial group that acts as an investment fund. It supports Poland’s economic development by investing in strategic projects (e.g., infrastructure, energy) and managing key government programs.

NCBR – The National Centre for Research and Development (Narodowe Centrum Badań i Rozwoju)

A government agency that bridges science and business. It provides grants to finance research and development (R&D), helping to turn innovative ideas into market-ready products and technologies.

BGK – Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego

Poland’s sole state development bank. It finances strategic national projects, such as infrastructure and energy, and supports the government’s economic policies and Polish exporters. It does not compete with commercial banks for individual clients.

Where can I learn more about startup funding?

This article is based on an episode from our Polish channel Pragmatycznie o… If you speak Polish, check this and other episodes.

What’s the very first source of money for most startups?

Usually, it’s the founders themselves–either their own savings or time put into building the product. After that, it’s often friends, family, or early believers (the “3Fs”: Friends, Family, and Fools).

What does “pre-seed” funding actually mean?

Pre-seed is the earliest outside money a startup raises–typically from angel investors or wealthy individuals. It’s often small checks to help get things off the ground before there’s much traction.

When do VC funds usually get involved?

Most VCs come in around the seed stage, when there’s a working product, early metrics, and something to evaluate. This is when due diligence starts to get serious.

How many funding rounds can a startup raise?

It varies–some raise just one or two, others go all the way to Series H or beyond. Each round usually comes with a higher valuation and a bigger check.

How do investors actually make money from startups?

Mainly through exits: IPOs or acquisitions. Dividends are rare in startups. Most investors wait years for that big payoff moment.

What is dilution and why should I care?

Every time you raise money and issue new shares, your ownership percentage shrinks unless you participate. That’s dilution–and it adds up fast if you’re not careful with your cap table.

What’s a cap table and why does it matter so much?

It’s a breakdown of who owns what in your startup. Keeping it clean and founder-friendly matters–because it affects your control, motivation, and future fundraising ability.

Who are LPs and GPs in a VC fund?

LPs are the money behind the fund–pension funds, governments, wealthy individuals. GPs are the people running the fund, choosing startups, and supporting them post-investment.

Is all VC money the same?

Not at all. Some funds are backed by private money, others by government programs. That affects how fast they move, how flexible they are, and when they have capital to deploy.

Can I raise money through crowdfunding?

Yes, but it’s not easy. Crowdfunding takes solid marketing, clear messaging, and often a lot of upfront work–even if the amounts raised are relatively small.

Why is funding in Poland different from the U.S.?

Poland’s VC scene relies heavily on public money (EU or government programs), while U.S. funds are mostly private. That means more rules, more structure, and different timing in Poland.

When’s the best time to raise money?

It depends on macro stuff–like interest rates and public funding cycles. Some periods are just better than others. Knowing the market context can save you months of wasted effort.